First-year medical students pose for a socially distanced class portrait. The 105 physicians-to-be received their white coats, considered the first symbolic step into the medical profession, and started their medical journey with family and friends watching remotely.

School of Medicine faculty knew that major shifts in the educational landscape would occur in 2020 with the rollout of a new curriculum. Three years in the making, the Gateway Curriculum would be the school’s largest and most comprehensive reform in decades.

What they didn’t expect was an earthquake in educational disruption — and months of aftershocks.

In March 2020, as dozens of faculty fine-tuned the Gateway Curriculum, readying it for a fall launch, the SARS CoV-2 virus aggravated its spread in the U.S., jolting much of the nation into unprecedented lockdowns.

Halfway through spring semester, COVID-19 safety concerns emptied the medical school. Nonessential employees scrambled to pack office and lab necessities for indefinite telecommuting. Lectures and labs, classes and clinical rotations came to a halt. Instead of spring-break downtime, many students moved back home, not knowing when they’d return; others quarantined in nearby apartments.

The urgency of the crisis left little time to tie loose ends or say goodbye to mentors and friends. Students wondered if they’d be able to finish their courses required for ascending to the next level of training.

“COVID-19 uprooted everything we were striving toward,” said Eva Aagaard, MD, the senior associate dean for education, who has spearheaded curriculum revision. “But we quickly realized it would not stop us from moving forward.

“Fortunately, we discovered our years of hard work designing the new curriculum and making the necessary investments in technology uniquely prepared us to transition from in-person to remote learning,” said Aagaard, also the Carol B. and Jerome T. Loeb Professor of Medical Education. “During the curriculum-building process, our collective mindset had become more accustomed to embracing change and innovation while pushing creative boundaries. These qualities made it easier to weather the abrupt move to distance learning and, more broadly, uncertainties surrounding COVID-19.”

The new curriculum prepared the medical school not only to survive but thrive during the rapidly changing, ongoing emergency crisis.

“Faculty felt the shock and stress. However, we knew we had no time to waste in transitioning academic instruction to an electronic platform,” said Thomas M. De Fer, MD, a professor of medicine and associate dean of medical student education. “Because of the planning and investments that had gone into revising the curriculum, we were able to do this efficiently and effectively.”

Targeted technology

Already in place was much of the medical school’s upgraded, top-of-the-line technology supporting video-based education and online interaction between faculty and students. Over a year earlier, the Instructional Design Studio opened in a 700-square-foot space in Bernard Becker Medical Library. It includes both a formal soundproof video-recording studio with green-screen technology and a smaller do-it-yourself studio. The space allows faculty to record lectures with supplemental and interactive features that the medical school can archive in a digital library and students can access at any time.

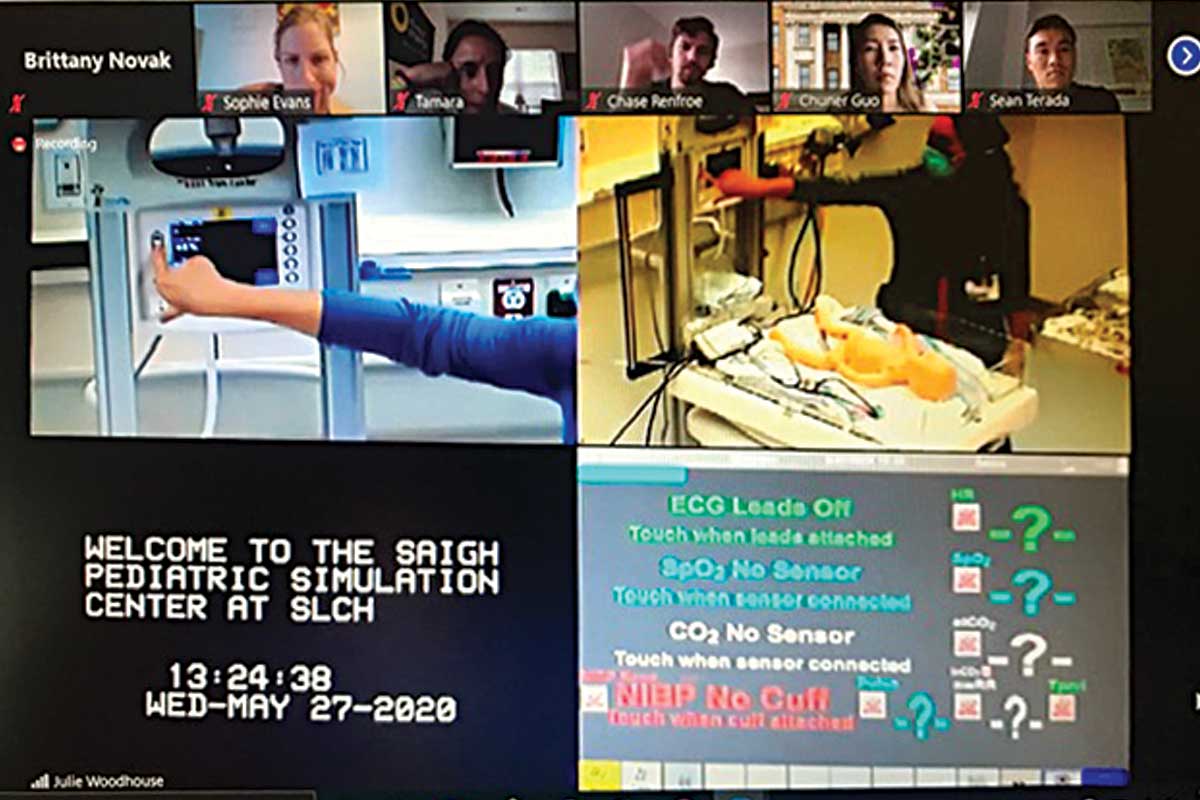

As part of their training, students direct treatment decisions through the school’s Saigh Pediatric Simulation Center. Computer screens offer multiple viewpoints of the patient.

“We have worked closely with faculty to examine how we will deliver parts of the new curriculum through video resources, and to create and produce dynamic, high-quality, clinically relevant video resources to enhance student engagement with course materials and promote meaningful, durable learning,” said Carolyn Dufault, PhD, assistant dean for educational technology and innovation in the Office of Medical Student Education.

Technology also enabled third-year clerkships to safely resume over summer. Students transported virtually to the school’s Wood Simulation Center, where rooms resemble clinical settings and mannequins serve as patients. Computer screens offered multiple vantage points of the patient and vital signs. Technician Brittany Novak operated the simulator and acted as the patient’s voice, while Julie Woodhouse, registered nurse and director of the medical school’s immersive learning centers, served as the bedside nurse, following the students’ patient-care directives.

“The clinical experience encouraged students to determine diagnosis and treat patients in acute scenarios in a safe setting and without faculty or residents instructing them on how to manage the situation,” Woodhouse said. “The experiences may have felt artificial or awkward, but I asked the students to think of it like telehealth or an electronic intensive care unit, where the physician is in a separate location from the patient and bedside staff. The pandemic has put a spotlight on telehealth. It’s likely to continue to play an increased role in patient care.”

Despite havoc wreaked by a global pandemic, the new curriculum launched in September with the 105 aspiring physicians comprising the entering class of 2020.

Larissa Lushniak of Rockville, Md., felt apprehensive beginning her first year of medical school with a new curriculum and during a pandemic. “But the use of innovative technologies and engaging virtual lectures have made learning extremely successful,” she said. “I’ve also found that learning clinical skills virtually has placed a greater emphasis on the importance of effective communication skills and forming strong physician-patient relationships. This is critical because, as physicians, we may see a patient in an exam room or virtually via telemedicine.”

Anticipated blips and bumps notwithstanding, Aagaard said the first few months of the curriculum rollout proved smooth. “The pandemic tested the new curriculum’s foundation,” she said. “Throughout, its pillars, its core values, demonstrated stability and strength.”

Watch as our incoming class of MD students begin medical school during the pandemic.

Gateway Curriculum

Health is determined, in part, by where people live, work, learn and play. Physicians today must possess an active understanding of these health determinants and navigate complex health-care systems. The Gateway Curriculum prepares students by integrating critical dimensions of practice: basic science, clinical skills, health systems science, social and behavioral science, and professional identity formation.

Academic excellence

- Scientific and clinical immersion all four years

- Competency-based curriculum & transparent assessment

- Emphasis on teaching quality, learning styles; technological enhancement

- Critical thinking, research & innovation

Individual development

- Multiple career pathways: Physician-researcher, educator, innovator, advocate, global health

- Customized, flexible framework

- Coaching relationships, mentors

- Student health & wellness — prioritizing self-care

Social justice

- Community engagement & service learning

- Health equity

- Diversity & inclusion

Learn more about the curriculum.

Published in the Winter 2020-21 issue