Some of the world’s most groundbreaking research on long COVID-19 can trace its origins to a 14-year-old Lebanese boy and his Commodore 64.

In middle school, Ziyad Al-Aly taught himself coding on his C64, a popular home computer introduced in the early 1980s. In high school, he solved complex mathematical equations and analyzed data using statistical applications. One day, Al-Aly decided to convert his C64’s internal clock to appear on his screensaver as an analog clock. Six months later, his screensaver boasted a dial and hours-minutes-seconds hands.

The project earned him first place in a youth coding competition.

Most importantly, the C64 helped Al-Aly realize his love for solving problems.

Over the decades, he has honed his digital talents. Al-Aly, MD, a nephrologist and clinical epidemiologist for the Institute for Public Health at Washington University School of Medicine, has become a leading COVID-19 researcher by tapping into big data and turning around studies within three to six months.

As director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center and head of research and development service at the Veterans Affairs (VA) St. Louis Health Care System, Al-Aly sifts through de-identified medical records of more than 10 million people in a database maintained by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the nation’s largest integrated health-care delivery system. This technique complements other important, but time-intensive, methods of scientific inquiry. Harnessing existing data and publishing findings in near-real time helps to inform public health and policy.

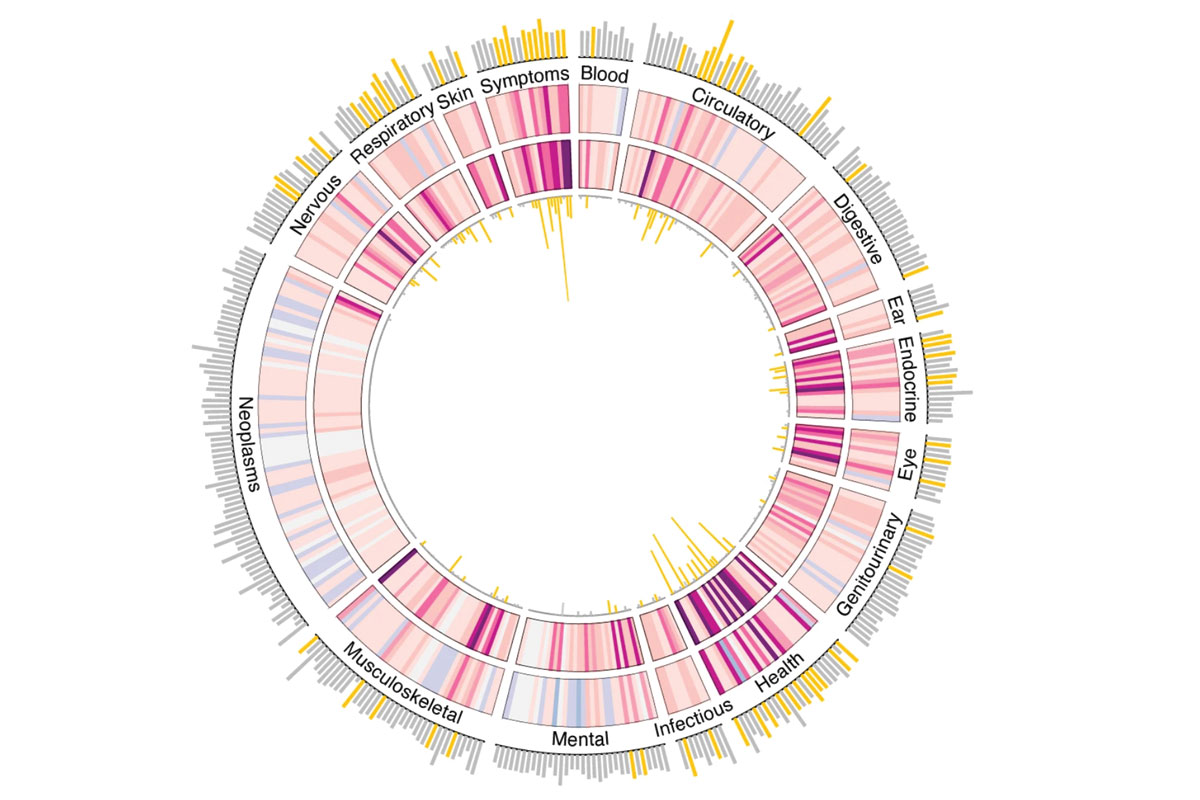

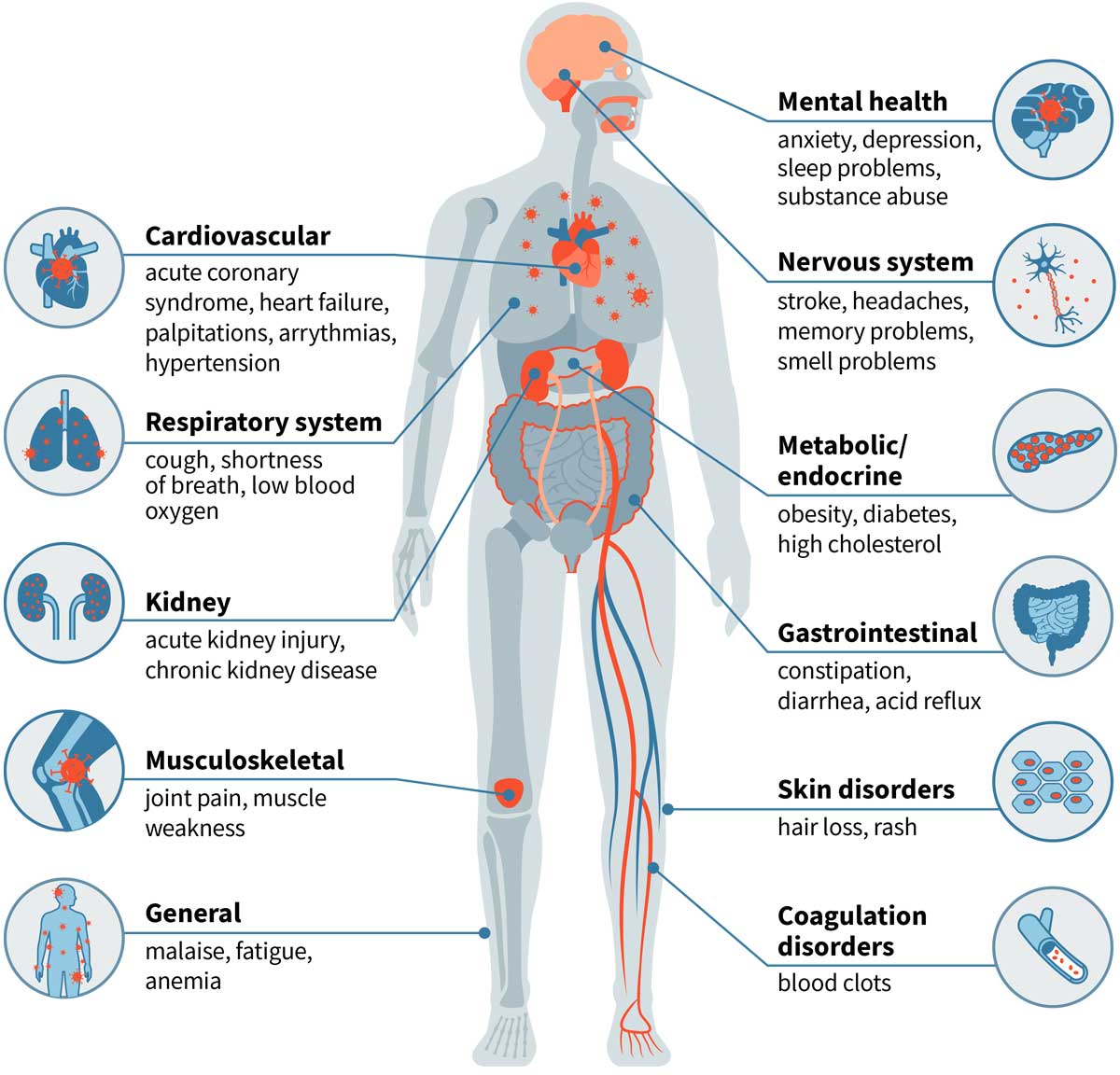

Using the federal data, Al-Aly’s research has found that people who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at higher risks of developing long-term — and potentially deadly — heart, brain, kidney, gastrointestinal and mental health problems compared with those who have not. Overall, people face significantly increased risks of organ failure and death within six months to a year after COVID infection. Post-COVID, people are also 40% more likely to develop Type 2 diabetes. That risk triples if they are hospitalized or admitted to the intensive care unit.

Additionally, Al-Aly’s research has shown that: COVID-19 is five times more likely than the flu to cause adverse health conditions; experiencing repeat COVID infections increases the risk of organ failure and death; and receiving vaccinations doesn’t shield those with breakthrough infections from developing long COVID.

His findings on long COVID have been published in top medical journals, such as The New England Journal of Medicine, Nature and the Journal of the American Medical Association, cited more than 10,000 times and featured in major media outlets, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, CNN, BBC and dozens more.

Several of his studies on long COVID have generated exceptionally high public and media engagement, ranking in the top 100 of more than 23 million research papers, according to Altmetric, a firm that monitors public engagement in academic research.

The White House took notice, appointing Al-Aly as co-chair of a committee tasked with developing the national research action plan on long COVID. He also advises the World Health Organization (WHO) and governments in the United Kingdom, Canada and other countries.

“Ziyad is at the forefront of extracting insights from massive databases,” said Harlan Krumholz, MD, a cardiologist, professor of medicine and director of the Center of Outcomes Research at Yale University. “He has leveraged complex and enormous data generated through clinical practice at the Veterans Administration to produce some of the most impactful epidemiological research. His work provides a real-world reflection of patient experiences, the effectiveness of treatments and opportunities to improve outcomes.”

‘The gravity of war’

The oldest child of teachers, Al-Aly’s youth was clouded by the religious civil war that dominated Lebanon from 1975 to 1990 — basically from the time Al-Aly was 2 years old until he began college. The family lived in a high-rise in Tripoli, in northern Lebanon, where “luckily for us, there was less fighting than in Beirut,” Al-Aly said. “But we weren’t without conflict.”

Once bombings started near their home, Al-Aly’s mother would take her three kids out of school to shelter in their building’s carpeted basement that doubled as a movie theater. Other children from the high-rise also sought safety there. “As kids, we didn’t understand the danger,” Al-Aly said. “We thought it was great fun. We didn’t have school or homework. We ran around and played. But that’s what my parents wanted: To shield us from the gravity of war.”

Worse than war, in Al-Aly’s mind, was his dad’s myeloma, a bone marrow cancer. “My dad was hospitalized frequently, and I vividly remember visiting him after school,” Al-Aly recalled.

Al-Aly was 16 when his dad died in February 1990.

“The doctors who cared for my dad showed me that medicine is about helping people and easing suffering,” he said. “They represented hope.”

Al-Aly decided he’d become a physician, too. “Being a doctor involves a lot of problem-solving,” said Al-Aly, 49, who treats patients at John J. Cochran Veterans Hospital. “I’ve always felt a strong desire to help people. My friends told me their troubles. These experiences taught me that listening is essential to solving problems.”

In 1999, Al-Aly earned a medical degree from the American University of Beirut. The following year, he immigrated to the U.S. for medical training in St. Louis, where scientific opportunities abounded.

He left his Commodore 64 in Lebanon.

“So many memories,” Al-Aly said. “But it wasn’t feasible to bring it to the states. With immigration, you leave one life behind and embrace the beauty and challenges of a new life.”

A collision of serendipity

Al-Aly’s love for clinical care, coding and data analysis collided serendipitously.

While a research fellow at Washington University, Al-Aly was on a J-1 visa, which allows grantees to stay in the U.S. for five years. Al-Aly’s mentor suggested he apply for a federal government job to facilitate acquiring a green card and U.S. citizenship. A few months later, in 2006, he became a kidney doctor and researcher at the VA St. Louis Health Care System, which has been affiliated with Washington University since 1946. Al-Aly is one of 120-plus School of Medicine physicians from numerous specialties who treat more than 70,000 veterans annually in the St. Louis region.

“I immediately knew VA data was special, an integrated and immense system,” Al-Aly recalled. “I would soon realize that the VA is the best place in the U.S. for data science at such a rigorous level.”

What distinguishes the VA database is its vastness, a one-stop shop that allows researchers inexpensively to capture health information such as medical diagnoses, labs, medications, behavioral habits and sociodemographic factors such as age, sex and ethnicity. While most veterans are older white men, the database includes millions of women and non-white people. With such a large population base, Al-Aly said statistical modeling can ensure parity in representation.

“The VA’s data is a national treasure that has helped us address important questions in near real-time,” he said. “It is a gift.”

Like his Commodore 64, the VA’s gift of big data has guided Al-Aly’s career.

Thousands of excess deaths

Yan Xie, PhD, MPH, was inspired to join Al-Aly’s team in 2014 because of his mentor’s approach to research: Listen to patients and the public to determine their concerns. Identify the problem. Use data to address it comprehensively and conclusively.

“Dr. Al-Aly dives into urgent health issues facing society — not just the scientific society, but the public at large,” said Xie, a senior clinical epidemiologist. “We approach our research with social responsibility. It’s why we work so hard. No one works harder than Dr. Al-Aly.”

Pre-COVID, Al-Aly conducted research on the effectiveness and adverse outcomes of commonly used medications including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), a popular class of heartburn drugs sold under brand names such as Prevacid, Prilosec, Nexium and Protonix.

More than 15 million Americans have prescriptions for PPIs, which provide relief by reducing gastric acids. Millions more purchase the drugs over the counter without being under a doctor’s care.

Al-Aly and his team analyzed de-identified medical records to identify veterans who had been prescribed PPIs and examined their health over a 10-year period. In 2016, he published his first PPI study, linking long-term use of heartburn drugs to chronic kidney disease. He later published research associating PPIs with adverse effects on the heart and digestive systems.

His landmark PPI study, published in The BMJ in May 2019, connected heartburn drugs to fatal cases of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease and upper gastrointestinal cancer. Al-Aly’s team found that such risks increase with the duration of PPI use, even when taken at a low dose.

“This translates into thousands of excess deaths every year,” Al-Aly explained.

The study mushroomed into a major news story, with media from The New York Times, CNN and NBC News courting his expertise. A news release about the study on the WashU School of Medicine website was the first to hit more than 1 million page views.

Listening to his patients, Al-Aly discovered another major concern: diabetes.

One of the fastest growing diseases, diabetes affects more than 30 million Americans, particularly people from poorer neighborhoods or countries who lack access to nutritious foods, recreational centers and health care. An unhealthy diet, sedentary lifestyle and obesity are among the major causes.

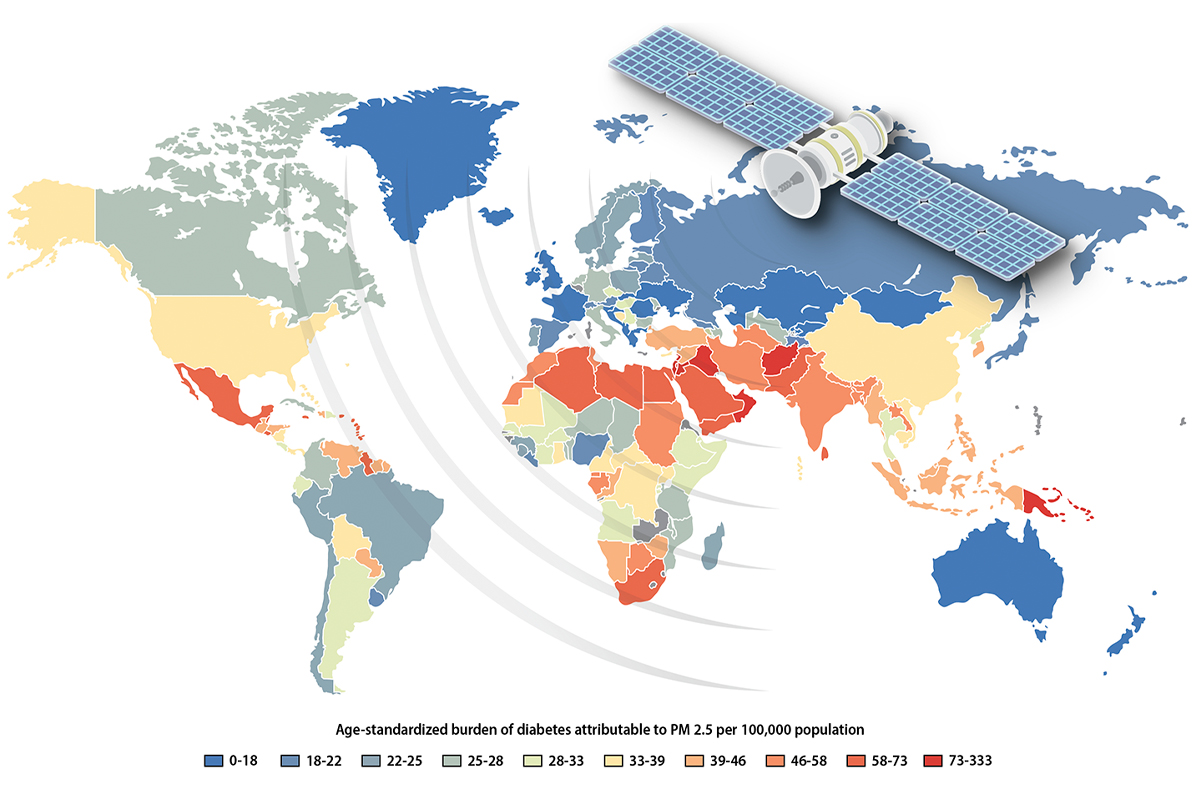

Al-Aly’s analysis of 1.7 million U.S. veterans with no history of diabetes revealed another significant driver: outdoor air pollution.

Pollution is thought to cause diabetes by reducing insulin production and triggering inflammation, preventing the conversion of blood glucose into energy needed to maintain health. “Prior research has suggested a possible link between pollution and diabetes, however, ours established a definitive link and quantified the relationship,” Al-Aly said about the study, published in The Lancet Planetary Health in 2018.

Al-Aly and his team devised statistical models to evaluate diabetes risk across various pollution levels. In addition to the VA records, the researchers culled data on particulate matter, airborne microscopic pieces of dust, dirt, smoke and soot from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), NASA and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

The findings linked air pollution to 3.2 million new diabetes cases globally in 2016.

“We found that pollution poses a higher risk of diabetes even at low levels of air pollution currently considered safe by the EPA and the WHO,” Al-Aly said.

Communicating science

When the pandemic arrived in early 2020, Al-Aly had no idea he’d been preparing for it his whole career. He called his research on PPIs and pollution “a training ground” for the 22 studies he has since published on COVID-19.

Conducting big-data research gave Al-Aly the experience to zero in on a topic, hone analytic techniques and engineer study designs — all within a short time frame. He’s learned to speak and write about science crisply and simply. He has emphasized data visualization to convey statistical outcomes. “I pay attention to detail, color and proportions,” Al-Aly said. “Whether it’s a chart, graph or sentence, the content of my research papers needs to tell a clear story so the general public and policymakers can be informed.”

At first, Al-Aly felt nervous talking with the media. Now he’s used to it. On average, he’s interviewed about 10 times a week. After he publishes a COVID study, the number can increase to 10 times a day. Once, he spoke, emailed and Zoomed with 15 reporters in a single day.

“Had the pandemic hit 10 years earlier,” Al-Aly said, “I wouldn’t have had the confidence to quickly wield such a massive amount of data, conceptualize statistical models and then explain it in lay language to media outlets worldwide.”

A legacy of chronic diseases

Once the U.S. went on lockdown in March 2020, Al-Aly felt the call of service. He treated COVID patients in intensive care units and, despite exposure, has yet to test positive for COVID. As a public health role model, he religiously wears masks.

He also rallied his researchers on Zoom. “We barely knew anything about SARS-CoV-2,” Al-Aly said. “But we wanted to help.”

Occasionally, Al-Aly heard talk among patients and physicians about lingering symptoms after a COVID recovery. Then, on April 13, 2020, he read a New York Times article about young, healthy people, post-COVID, plagued by coughs, shortness of breath, brain fog and other symptoms.

Through online research, he discovered the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, an international support group of biomedical researchers, policymakers and data analysts who have experienced long COVID. Many have been dismissed by doctors.

But Al-Aly immediately activated his team to conduct multiple studies on long COVID.

“Ziyad was one of the first researchers to take actionable steps based on our experiences as patients,” said Hannah Davis, the group’s co-founder. “He has produced some of the earliest and most comprehensive research on long COVID. Ziyad helped to change clinical care by showing doctors that long COVID is a real condition, not just something in patients’ heads.”

In January 2023, Davis helped publish a study estimating that long COVID affects at least 65 million people worldwide.

At Washington University, Al-Aly has led grand rounds on identifying and treating patients with long COVID. His studies also have influenced the School of Medicine’s Post COVID-19 Clinic, which offers a multidisciplinary approach to caring for long COVID.

“Dr. Al-Aly’s work has been monumental in understanding the clinical manifestations after COVID-19 infections and informing patients to recognize their own symptoms,” said Gayathri Krishnan, MD, an instructor of medicine and a fellow in medical education who leads the Post COVID-19 Clinic. “His findings on long-term brain and heart conditions after COVID-19 have helped us evaluate and better care for our patients.”

Additionally, Al-Aly’s research has served as the foundation for long COVID guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other global government entities.

“Long COVID is leaving a legacy of chronic diseases,” Al-Aly said. “Health systems and governments need to be prepared for the long-lasting consequences for patients, health systems, life expectancy and economic productivity. Addressing challenges posed by long COVID will require economic investments and a coordinated, long-term global response strategy. So far, that is lacking.”

Al-Aly recommended the federal government create a data center to generate evidence in near real-time to help address future challenges. “It would be a huge missed opportunity if we go through this pandemic without learning from it,” he said.

His reasoning harkens back to the months he spent as a teenager trying to create an analog clock on his computer: “Thinking deeply, my Commodore 64 represents my lifelong passion for solving scientific problems.”

Published in the Spring 2023 issue