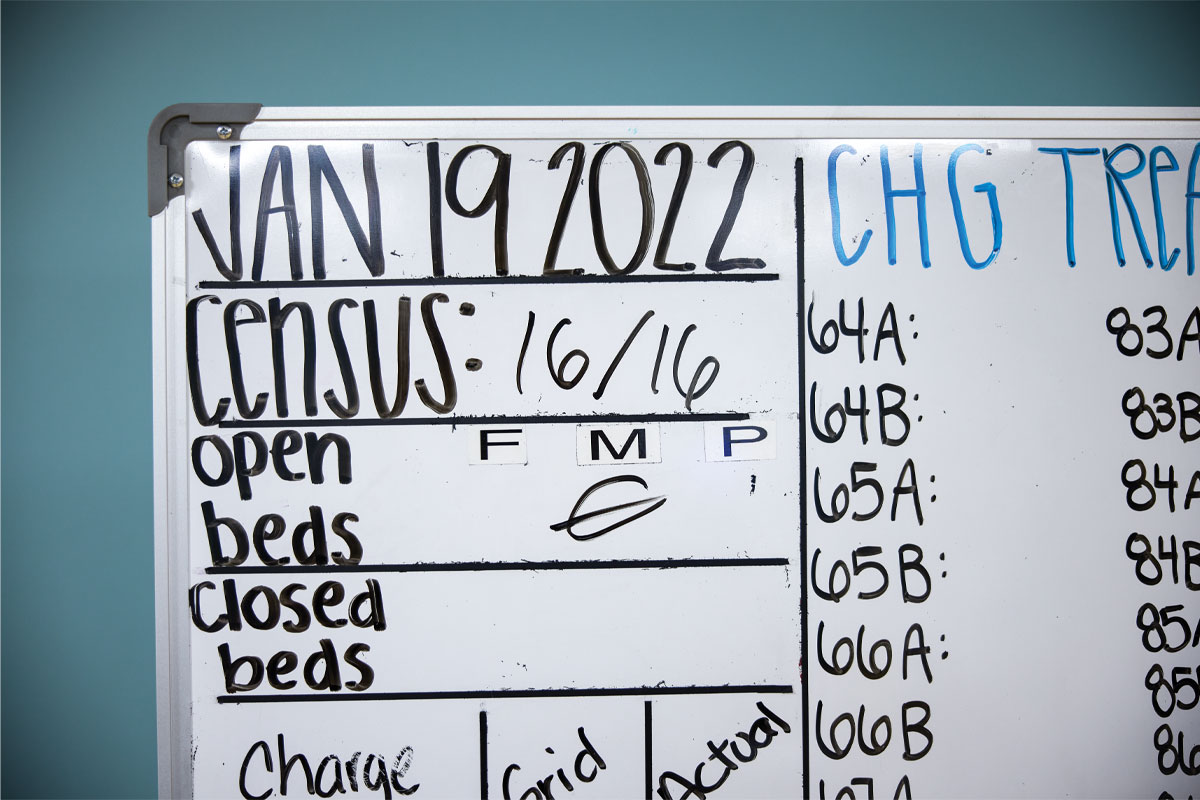

Barnes-Jewish Hospital, like hundreds of other urban hospitals across the nation, was at capacity during the most intense days of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the Medical Campus, health-care workers at all levels of expertise and in every specialty were pushed to their limits. And among those serving almost beyond their own expectations were the hospitalists — physicians who specialize in treating hospitalized patients. Working around the clock, they ensured excellent care for every medical floor patient with COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic and subsequently coordinated care delivery for the majority of them throughout the pandemic.

The pandemic didn’t define the role of hospitalists. But, for patients, families and even other health-care providers, it did highlight the key role these specialists play in inpatient care. Yet, hospitalists have been important to inpatient care for decades. The School of Medicine’s Division of Hospital Medicine, established in 2000, is one of the largest academic divisions of hospital medicine in the U.S., with more than 100 hospitalists caring for inpatients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Barnes-Jewish West County Hospital.

Mark V. Williams, MD, took the helm of this still-expanding division in the midst of the pandemic, as chief and a tenured professor of medicine in October 2021. One of the most respected leaders in the field, he established in 1998 the first hospitalist program at a public hospital, Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Having built large hospitalist programs at three other academic medical centers, authored or co-authored 200-plus publications and received more than $34 million in grants and contracts, he is enthused about leading the Washington University program forward as a national model.

“Hospitalists play an integral role in quality improvement and patient experience and are an important part of our medical education mission,” Williams said. He noted that hospital medicine is the fastest growing specialty in the history of American medicine — now larger than emergency medicine or cardiology. Nonetheless, many people are still unaware of hospitalists’ scope of care.

Consider the hospitalist like a symphony conductor. Each hospitalized patient requires care from a team. The specialists, nurses, therapists and social workers assigned to a patient’s case are like individual musicians, each expertly playing a part. The hospitalist conducts this medical orchestra, ensuring that all parts are working harmoniously to produce optimal patient outcomes. The hospitalist also communicates with the patient’s primary care physician and family caregivers, keeping the entire care team on the same page regarding diagnostic history and follow-up care.

Hospitalist history

Before the term “hospitalist” was coined, Barnes-Jewish Hospital offered a precursor known as the private medicine service. “We were the hospital’s house physicians, helping private-practice primary care doctors provide care for inpatients,” said Mark S. Thoelke, MD, professor of medicine. “The model, even in the mid-’90s, allowed us to be hospital employees with a strong teaching role.”

In 1996, Robert M. Wachter, MD, now professor and chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, first used the term “hospitalist” in an article published in The New England Journal of Medicine. Considered the “father of hospital medicine,” Wachter is a longtime friend of Williams’ and, earlier this spring, visited Washington University to discuss the future of medicine with hospitalists here.

“It dawned on me that the way we organized medical care just wasn’t working,” he said of his original publication. “Hospitals are very complicated, and things happen very quickly. We needed a new model, and there just wasn’t a specialty focused on the care of hospitalized patients. We needed physicians who were generalists comfortable dealing with many problems, but whose specialty was dealing with patients in this complicated hospital structure.”

Under the leadership of John P. Lynch, MD, now president of Barnes-Jewish Hospital, Thoelke served as the first clinical director of the Division of Hospital Medicine from 2000 through 2009, then took over as division chief for the next 11 years. “In 2020, I decided it was time to return to the activity I love most — teaching,” he said.

During his tenure, the division launched some of its most significant areas of contribution. Notably, it collaborated with Siteman Cancer Center to provide clinical inpatient services for oncology. About two-thirds of all patients with cancer admitted to Barnes-Jewish now receive care from hospitalists. And it also began teaching house staff to perform bedside procedures. Division hospitalists are leaders in medical education for both students and residents, winning awards every year.

Both the cancer care and the teaching initiatives mark evolutions in the specialty that other programs are emulating. “It’s been satisfying to develop our educational mission alongside our clinical efforts,” said Robert J. Mahoney, MD, associate professor of medicine. He and Thoelke are two of the five original physicians who formed the nascent division in 2000.

An attractive specialty

Given the weight on hospitalists’ shoulders in the last few years, it might be surprising that the specialty continues its rapid expansion. But medical students tend to base residency decisions on their clinical rotation experiences and also note the satisfaction levels of attending physicians and faculty working in those specialties, Williams said. Hospitalists, he said, often express positive feelings about their work and demonstrate work-life balance. Though schedules vary, a hospitalist on service may work long hours for seven consecutive days and then be off service for the next seven days, as an example.

“When we have great role models who are educating and guiding our medical students through their first exposures to inpatient care, the hospital medicine specialty is very attractive,” Williams said. The path to becoming a hospitalist typically involves residency training in general internal medicine, general pediatrics or family medicine.

Stephanie Conner, MD, assistant professor of medicine, is among the younger generation of hospitalists at Barnes-Jewish Hospital joining the service this year. “I chose hospital medicine because I love the acuity and breadth of medicine that you see in our role; every day is interesting and no two days are the same,” she said. “I’ve also begun to appreciate the diverse career that you can have in hospital medicine through opportunities in medical education, quality improvement, clinical operations, hospital leadership, patient advocacy and research.

“The value of hospitalists is not just in our ability to care for patients in the acute care setting, but our ability to contribute to how the hospital functions in all of those areas,” she added.

Increasing care efficiency

Williams has spent his career researching and documenting hospitalists’ contributions to patient throughput and care transitions. This interest began when he observed discharged patients being readmitted, often due to failure to fill prescriptions and obtain follow-up care.

“I realized that we did a poor job of educating patients who were being discharged from the hospital,” he said. “That lack of health literacy correlated with readmission and even increased mortality. I became interested in optimizing the transition from emergency department to inpatient service to outpatient care.”

A key component to improving care transitions is strengthening the connection between hospitalists and primary care physicians. Many patients expect to see their family doctor or internist while in the hospital, but this expectation adds increased pressure to a field that is experiencing national shortages. Primary care physicians are ever busier with more complicated patients in their ambulatory practices. These forces have led primary care doctors to stop rounding on their hospitalized patients.

To improve care efficiency and alleviate stress, it is imperative that patients understand how hospitalists fit into their care team and develop trust that their doctors are working together. Williams recalled that while working at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, he learned from a geriatrician who interviewed patients about their understanding of hospitalists. The takeaway: “Patients trusted their primary care physicians and needed to check with them before filling new prescriptions I had ordered,” Williams said. “They did not trust me initially. That makes sense, and I took that to heart in showing how critical it is for the hospitalist and the primary care physician to communicate during patient hospitalizations.”

Williams subsequently strived to ensure that hospitalized patients received at least a brief phone call from their primary care physician to clarify that everyone was working toward their benefit. This team approach also applies to other community care providers, such as home health nurses, Williams added, describing the stepwise progression of his research to understand and address care transitions between clinical settings.

“One of the first grants I received was to develop a patient safety toolkit,” he said. “That work led to the development of Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Optimizing Safe Transitions), which was funded in 2008 and eventually implemented at more than 200 hospitals. At the same time, I worked with colleagues to publish data about care transitions, which showed that one in five Medicare patients were readmitted after discharge. That influenced the hospital readmission reduction program written into the Affordable Care Act.”

One of Williams’ goals for the Washington University hospital medicine program is to further reduce readmissions and optimize throughput — the movement of the patient from an inpatient care setting to the next appropriate location, whether a rehabilitation center, long-term care facility or home. To achieve this, Williams is initiating teams to work on improving care transitions, reduce readmissions, enhance patient throughput and to reduce patient delirium.

“We’re both improving care delivery and training hospitalists in quality improvement measures; we want to build an army of physicians who are skilled and dedicated to improving patient care,” Williams said.

During the pandemic, hospitalists more than proved their worth as team players, said Victoria J. Fraser, MD, the Adolphus Busch Professor of Medicine and head of the Department of Medicine. “They stepped up and provided the vast majority of care for COVID-19 patients who were admitted to the medical service, even creating a handbook and guidelines for managing non-ICU COVID-19 patients and educating other specialists,” she said.

Fraser referred to hospitalists as the “unsung heroes” of the pandemic, relieving the burden on other specialists who needed to continue care for their non-COVID-19 patient populations, as well as consult on COVID-19 cases.

Both Williams and Fraser recognize Michael Y. Lin, MD, as one of the hospitalists going above and beyond during the pandemic’s early days. Lin, who served as interim division chief prior to Williams’ arrival, purchased as much protective equipment as he could at local hardware stores when the first surge was straining hospital supplies. “He did just an extraordinary job of shoring up and encouraging his colleagues,” Fraser said.

Han Li, MD, assistant professor in medicine, was another hospitalist leader during the pandemic, Fraser said. “Dr. Li jumped onto the front lines when we didn’t really know how to treat COVID-19 or what caused it. She was brave and dedicated as she started to figure out how the hospitalists could step up and manage these patients.”

An ongoing need

Hospital medicine continues to expand for reasons other than physician satisfaction and interest. “Hospitalized patients are increasingly sicker and more complex, requiring a higher level of care on the floor,” Williams said. “And there are also sicker outpatients demanding more of their primary care physicians. With the more complicated inpatient population, there needs to be a physician available on site at all times, and we’re there, partnering with nurses, pharmacists and therapists to make sure care is coordinated and complete.”

Adding to a more efficient inpatient care structure, many Washington University hospitalists provide bedside tests and procedures, reducing the need to transport patients from their rooms to another part of the hospital. Patients prefer to undergo procedures in their rooms when possible.

“A lot of places struggle to maintain a procedure service in their hospitalist division, but we’ve been doing it and sustaining it successfully for years,” Mahoney said.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is becoming more common and better at diagnosing pneumonia and heart failure than traditional bedside exam modalities. POCUS may soon even replace stethoscopes. Other procedures performed by hospitalists at the bedside include placing central lines; removing fluid from joints, around the lungs and the abdomen; and lumbar punctures.

“Even before the pandemic, our hospitalists were recognized as outstanding clinicians,” Fraser said. “Still, people don’t have the best understanding of how hard it is to be a hospitalist and what exactly they do. They care for the sickest of the sick, they work long shifts with lots of patients, and they make sure things run as efficiently as possible.”

Williams agrees about the quality of his hospitalist colleagues at Washington University. “We have a huge opportunity here, and we’re already one of the best hospitalist programs in the nation. We can be one of the country’s top five programs within the next five years through pursuit of scholarship and grant funding,” he said.

Williams plans to continue developing relationships with primary care physicians throughout the region and with the patients they serve. He noted the growth of the home hospital movement, in which patients receive hospital-level care in the home. In these hybrid care models, hospitalists and nurses make home visits and monitor vital signs through devices that deliver remote patient data.

“A review of international studies in 2012 showed that delivering hospital-level care in patients’ homes resulted in reduced cost, mortality and rehospitalizations. A randomized controlled trial performed in the U.S. and published in 2019 showed much higher patient satisfaction and reduced costs and rehospitalizations from a hospital-at-home program,” Williams said. He looks forward to hospitalists helping to build such a program here.

Looking further down the road, Williams sees hospitalists focusing their care on specific patient populations. For instance, one of the hospitalists’ largest services is oncology. About a third of all the hospitalists at Barnes-Jewish focus on this care. Other potential areas of specialization include co-management of patients on surgery, psychiatry, critical care, cardiology and palliative care services.

“The fact is, hospitalists have become crucial to the function of hospitals and to the best results for hospitalized patients,” Williams said. “We’re here, we’re staying, we’re ready to step up as needed, and that serves everyone.”

Published in the Autumn 2022 issue