Pediatric pulmonologist Thomas Ferkol, MD, had long been suspicious of the safety claims made for electronic cigarettes. But until a few years ago, vaping had not riveted his attention. Ferkol’s focus is on children, and he assumed the devices were for adults trying to kick their addiction to combustible (tobacco) cigarettes.

“I did not truly understand the problem until I was talking with the mother of a child with asthma,” recalled Ferkol, the Alexis Hartmann Professor of Pediatrics at the School of Medicine. “I asked if anyone in the family had been using e-cigarettes. The mother was surprised by the question, saying I was the first physician who had ever asked.”

The mother reported no one in the family used the devices but added that she was a teacher in a suburban school district and that e-cigarettes were a huge problem in her class. She had a drawer full of devices she had confiscated from her students.

Afterward, Ferkol began to review the medical literature and made a stark realization: “We were in the midst of a growing epidemic of nicotine addiction in children and adolescents,” he said. “We did not fully grasp what these products were doing to their lungs, and no one was talking about it.”

Ferkol was not the first to recognize the problem. But because of his prominent role in the American Thoracic Society and his relationship with other professional organizations worldwide, he knew he had a better opportunity than most to warn others about the threat e-cigarettes posed to teenagers.

That was four years ago. Since then, Ferkol has spoken frequently about the growing epidemic of e-cigarettes with youths, sounding the alarm again and again. On behalf of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS), a collaborative of global respiratory disease experts, he was first author on a position statement about the threat of e-cigarettes to adolescents.

Ferkol and other School of Medicine physicians are aghast at how quickly vaping has taken hold among adolescents after a charmed decade when young people were turning away from combustible cigarettes.

“What we are hearing now is really alarming,” said Patricia Cavazos, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry. She has studied the impact of e-cigarette marketing on youth as part of addiction research supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1.5 million adolescents were using e-cigarettes in 2017. By 2018, that number more than doubled to 3.6 million. “The data show that one in five middle schoolers and one in three high school students are vaping,” Cavazos said.

Concern began to rise with reports of mysterious lung infections that were sending young people to emergency rooms. The CDC has linked vaping to 2,291* cases of lung damage illnesses and 48 deaths. While the cases are still being investigated, doctors nationally are suggesting that the injury pattern and tissue damage resemble a chemical burn or toxic chemical exposure injury. The condition is now known as EVALI (e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury).

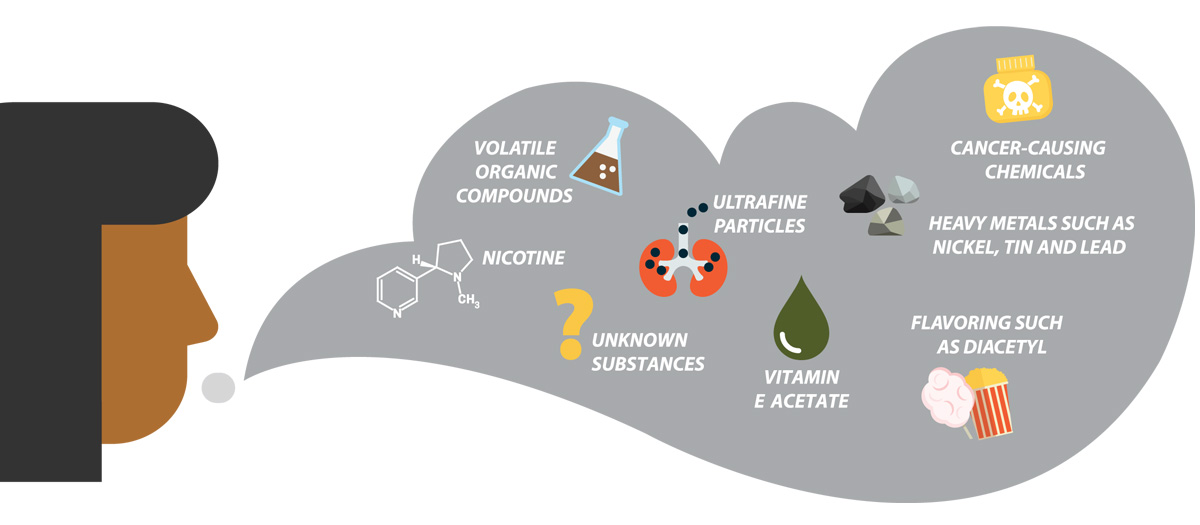

People also use e-cigarettes to smoke marijuana, and black-market products containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) have emerged as a primary suspect in the injuries. In November, the CDC reported vitamin E acetate as a chemical of concern in EVALI. The sticky additive is used as a thickening agent in THC vaping products.

The cannabis issue aside, researchers say that it may take 20 years to fully discern the effects of inhaling heated e-cigarette liquids.

The battery-operated devices include a reservoir for holding liquid that typically contains nicotine, a heating element or an atomizer, and a mouthpiece. It heats the liquid into an aerosol that is inhaled by the user.

The enormous variability in the product category — with differing chemicals, devices and nicotine levels — makes public health recommendations challenging.

E-cigarettes do contain far fewer toxins than combustible cigarettes. However, Ferkol said, electronic cigarette aerosols are not simply “harmless water vapor,” but contain noxious and potentially harmful ingredients, including ultrafine particulates, volatile organic compounds and heavy metals, such as nickel, tin and lead.

“Other reports have shown that these products can be contaminated with bacterial and fungal toxins. It is quite possible that recent respiratory complications are related to existing or newer chemicals or flavorings, some known to be injurious to the lung,” he said.

Still, the number of people vaping is increasing markedly — and not because of the original intent: to wean adult smokers off combustible cigarettes. Youth and young adults use e-cigarettes more than any other age group.

An e-cigarette brand called JUUL launched in 2016 with a novel nicotine formulation, assorted flavors and a stealthy device. Sales among young people soared. JUUL now owns half the e-cigarette market.

Before JUUL’s launch, e-cigarettes relied on bottled liquid containing nicotine, flavorings and a humectant such as vegetable glycerin or propylene glycol. JUUL introduced pre-filled, pocket-sized pods that are fueled with a nicotine-salt formulation.

A single pod delivers as much nicotine as a pack of 20 cigarettes. Depending on usage, a pod (about 200 puffs) typically can last from one half-day to more than one week. The brand’s commercial success, with its high nicotine concentration, is generating copycat products.

Nicotine salts are known to produce a smoother, more pleasant hit. “It’s easier to inhale nicotine-salt vapor than other e-liquids or tobacco products, which can be quite harsh,” Cavazos said. “So, it becomes easier for non-smokers to ingest these newer products.”

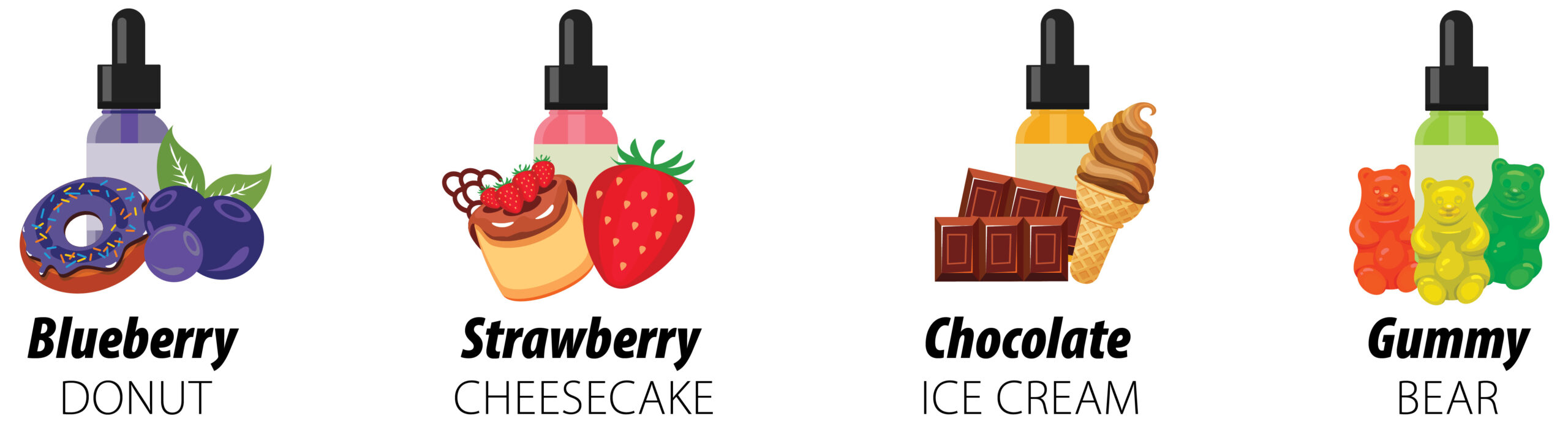

Adolescents identify flavoring as a prime reason they experiment. A November 2019 NIH analysis suggests teens prefer mint and mango as their vaping flavors of choice.

Amid rising concerns, manufacturers now are significantly limiting flavors, and a number of states are enacting bans on vaping flavors. At one point, e-liquids came in more than 7,000 flavors, among them cotton candy, bubble gum, gummy bear and cherry crush.

The JUUL device, which looks like a USB flash drive, is sleek and discreet, and can be easily hidden from teachers and parents. Perhaps this is why 10% of middle and high school students in a recent survey cited the “cool factor” as a reason they started experimenting with e-cigarettes. Students routinely vape during class, as nicotine salts do not generate a huge plume of smoke.

E-cigarette companies market the devices through Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, mobile and TV ads, and even use scholarship offers as a way to recruit youth users.

Sarah Garwood, MD, associate professor of pediatrics and adolescent medicine, sees adolescents from across the region in her practice. She estimates that a quarter have tried vaping or are doing it regularly. Most weren’t smoking cigarettes, so they had no need to use a device touted for properties that would help a user kick the combustible habit.

Susceptibility to addiction

In fact, combustible smoking rates, alcohol use and illicit drug use among youths have been going down for 20 years. “We have had a great public health success by reducing combustible cigarettes among adolescents,” said Laura Bierut, MD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Psychiatry, who also sits on the FDA Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee.

Cavazos questions whether e-cigarettes might negatively impact this progress. “The rapid uptake of e-cigarettes has taken us by surprise,” she said.

One substance that concerns both investigators is marijuana. As marijuana continues moving into the mainstream, the new technology of e-cigarettes has given young people more ways to consume it.

Vaping THC (the primary psychoactive ingredient in marijuana) does not produce the telltale smell associated with smoking a joint or blunt — potentially allowing users to escape negative stereotypes and detection. Users consume even higher THC concentrations when they vape rather than smoke, which means greater exposure to the drug’s mind-altering and addictive ingredient. Also, the drug often is purchased through less-than-reputable sources.

“The implicated vaping products were marijuana products. And marijuana use is increasing in adolescents,” Bierut said.

Marijuana, she added, has been linked to increased risk for mental illness, including psychosis/schizophrenia, depression and anxiety. With vaping, the health risks of e-cigarettes and cannabis compound each other.

“Adolescent brains are more susceptible to the addictive qualities of a substance,” Bierut said. “Once addicted to one substance, it is easier to become addicted to another substance, such as alcohol and marijuana.”

For those who aren’t already smoking combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes potentially could become a pathway to nicotine addiction.

In the report Ferkol delivered for FIRS, he and his co-authors highlighted concerns about repeated nicotine exposure in youths: “The central nervous system undergoes structural and functional adaptations, such that the brain requires nicotine to function normally … . Several lines of evidence indicate that nicotine exposure during adolescence may have lasting adverse consequences for brain development.”

Researchers say they need more data about nicotine’s impact on the developing brain. “Especially for young people, their brains are developing at a very rapid pace,” Cavozos said. “It’s possible that nicotine use can change the wiring of young people’s brains, and could lead to problems with cognition, learning, memory and other mental health issues. We need to better understand the negative consequences.”

Smoking, with its addictive qualities, has been around for a very long time. For tobacco manufacturers, the goal was to get people to try the product. That initial impression — that first drag of a cigarette — might not be so wonderful. But if peers are doing it, and if marketing suggests that it’s glamorous (in the 1940s), cool (in the 1950s) — and at one point touted as healthy and safe — people might smoke until they’re hooked.

When the surgeon general’s report arrived in 1964 saying that cigarettes “could be hazardous to your health,” many Americans decided to “kick the habit.” That proved to be difficult, so difficult that it eventually created another market for devices that would help.

Does using e-cigarettes help people quit smoking? Evidence is limited. Current research, in fact, confirms dual usage of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes in all age groups, from young users to adults. This suggests that people may be using the products interchangeably, supplementing — not replacing — tobacco smoking with vaping.

Yet, some committed adults are successfully using e-cigarettes to wean themselves from combustible cigarettes. “The American Cancer Society has a good policy statement on this,” Bierut said. “If you are a combustible cigarette user, you should quit. If you choose not to quit, have a harm-reduction approach; the standard e-cigs are safer than combustible cigarettes.

“Simply put, vaping can be helpful if you quit combustible cigarette smoking and can be dangerous if you use rogue products.”

The FDA has urged the public to avoid using THC-containing vaping products or products obtained off the street. The agency’s Forensic Chemistry Center is working closely with federal and state partners to identify substances that may be causing illnesses.

The FDA now stipulates that buyers must be 18 years of age and present a photo ID.

Mitigating a menace

The question is whether any of the current regulations and restrictions are effective. And the answer is: not very. Ferkol has found vendors employ weak verification measures. “It’s almost laughable,” he said. In some cases, internet sites simply ask a consumer to fill in the year he or she was born. “If a student doesn’t know how to dodge that verification step it suggests a failure of the American education system,” he joked.

Ferkol wants to see much stronger measures: regulating nicotine-delivery systems in the same way as tobacco products; barring the sale of e-cigarettes to adolescents, while also providing rigorous enforcement; regulating advertising; eliminating flavorings; and conducting ongoing studies to better understand the threat that e-cigarettes pose to youth.

In the meantime, parents and physicians need to help mitigate the menace to public health. Studies show that many adolescents don’t believe e-cigarettes are dangerous, and some assume they are comprised mostly of flavoring.

“There is speculation that e-cigarettes are healthier than regular cigarettes because they don’t burn tobacco, but they are by no means healthy,” Cavazos said. “Too many youths believe these products are healthy.”

When an adolescent is discovered with a vaping product, parents should get a health professional involved to educate about the risks, and, if necessary, prescribe smoking cessation medication or counsel about nicotine addiction.

Every health-care provider should ask young patients whether they or anyone in their home are vaping. “I talk to all of my patients about the risks whether or not they are vaping or smoking other substances,” Garwood said.

Garwood strongly advises patients to quit immediately or to set goals for quitting — perhaps by cutting back and picking a quit date. That’s when the patient is instructed to remove vaping products and substitute a healthier habit.

Looking ahead, Ferkol said he cannot predict whether e-cigarettes will be legislated out of existence. He acknowledges that some believe e-cigarettes could be a useful tool for smoking cessation in adults who are committed to quitting. However, with the surge of respiratory illnesses, he “truly hopes our policymakers recognize the threat and address this public health issue much more carefully.

“I’d like to think in time we will come to a general consensus as to what their place is in society. But until we understand the short- and long-term deleterious effects of e-cigarettes, they need to be closely regulated and kept out of the hands of children.”

Richard H. Weiss is a freelance writer who worked as a reporter and editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 30 years. Sally J. Altman, MPH, is a journalist specializing in public health and racial equity issues. Deb Parker is editor of this magazine.

Published in the Winter 2019-20 issue