While Zika virus causes devastating damage to the brains of developing fetuses, it one day may be an effective treatment for glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer. New research from Washington University School of Medicine and the University of California San Diego School of Medicine shows that the virus kills brain cancer stem cells, the kind of cells that are most resistant to standard treatments.

“We showed that Zika virus can kill the kind of glioblastoma cells that tend to be resistant to current treatments and lead to death,” said Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine at Washington University and the study’s co-senior author.

The findings are published Sept. 5 in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The standard glioblastoma treatment is aggressive — surgery, chemotherapy and radiation — yet most tumors recur within six months. A small population of glioblastoma stem cells often survives the onslaught and continues to divide, producing new tumor cells to replace the ones killed by the cancer drugs.

In their neurological origins and near-limitless ability to create cells, glioblastoma stem cells reminded postdoctoral researcher Zhe Zhu, PhD, of neuroprogenitor cells, which generate cells for the growing brain. Zika virus specifically targets and kills neuroprogenitor cells.

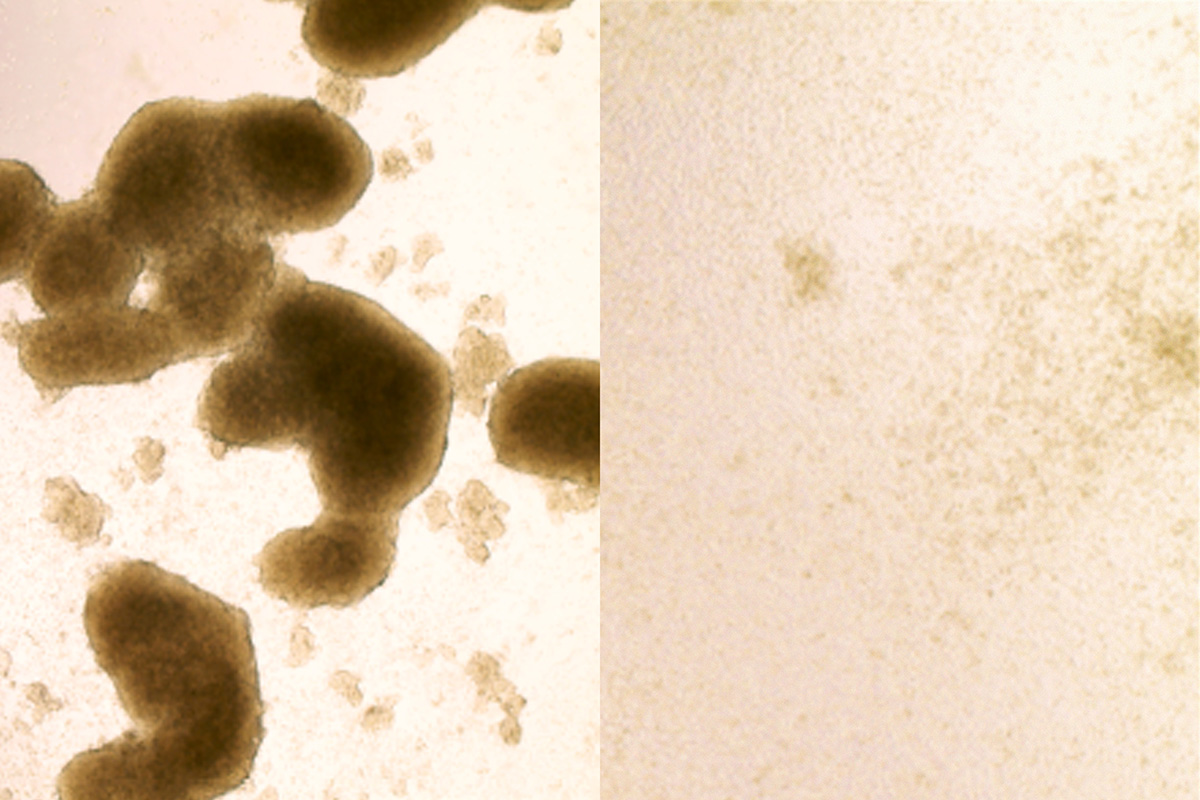

Collaborating with co-senior authors Diamond and Milan G. Chheda, MD, of Washington University, and Jeremy N. Rich, MD, of UC San Diego, Zhu tested whether the virus could kill stem cells in glioblastomas removed from patients at diagnosis. They infected tumors with one of two strains of Zika virus. Both strains spread through the tumors, killing the cancer stem cells while largely avoiding other tumor cells.

From left, brain cancer stem cells before and after Zika treatment. A new study shows that the virus, known for killing cells in the brains of developing fetuses, could be redirected to destroy the kind of brain cancer cells that are most likely to be resistant to treatment.

The findings suggest that Zika infection and chemotherapy-radiation treatment have complementary effects. The standard treatment kills the bulk of the tumor cells but often leaves the stem cells intact to regenerate the tumor. Zika virus attacks the stem cells but bypasses the greater part of the tumor.

To find out whether the virus could help treat cancer in a living animal, the researchers injected either Zika virus or salt water (a placebo) directly into the brain tumors. Tumors were significantly smaller in the Zika-treated mice two weeks after injection, and those mice survived significantly longer.

The idea of someday injecting a virus notorious for causing brain damage into people’s brains seems alarming, but Zika may be safer for use in adults because its primary targets — neuroprogenitor cells — are rare in the adult brain. The fetal brain, on the other hand, is loaded with such cells, which is part of the reason why Zika infection before birth produces widespread and severe brain damage.

Q&A with with Mike Diamond and Milan Chheda

How did you come up with the idea of using Zika to treat glioblastoma?

Diamond: It was really the idea of Zhe Zhu, who was a postdoc with Jeremy Rich. He emailed me several times and said he wanted to do it. I said, “That’s crazy, I don’t want to do that.” Because I knew that a related virus — West Nile — had been tried 50 years ago and it made things worse. It caused serious brain infections and did not cure the cancer. So I said, “That’s not going to work. That’s not safe.” But he kept on asking until I agreed to let him try. Jeremy sent him over to my lab for what was supposed to be three months and turned into a year. And at some point we gathered enough data to look at which cells were being infected and found that it was not replicating throughout the brain and then I no longer had reservations. After we had established that the virus could specifically infect the stem cells, we needed someone with neuro-oncologic expertise. Milan took on a major role at that point.

What has been the response to the study?

Chheda: We’ve received emails from patients all over the world. They say that their loved ones or a friend or they themselves are in this dire situation and ask if they can try Zika. We tell them that it’s not FDA-approved, it hasn’t been proven safe or effective, but some people say they understand that and they want to try it anyway. We’ve been asked if we can bring the virus to some other place, like Mexico, where FDA rules don’t apply so they can try it. And of course we can’t do that, but it just goes to show how desperate people are for any bit of hope.

What do you say to the people who contact you?

Chheda: I ask if they want to speak on the phone. They tell me about their current treatment or plans for treatment. The one thing that stands out is that throughout the world, almost everyone is treated the same way when they are first diagnosed. And universally the situation is dire no matter where you live. I tell them that we’re working on getting to human trials, but we’re talking about at least a year and a half before anything could potentially be tested in humans.

What do you have to do before you can test it in people?

Diamond: We are trying to get some guidance on that from the FDA. Because of the dire nature of the disease, the bar might not be as high as we thought. The key issue, of course, is safety. Although discussions are planned, the FDA likely will require that giving Zika doesn’t make things worse in mice, and that we can manufacture the virus according to good manufacturing practices. But they may want more, too; it’s not totally clear yet.

Published in the Winter 2017-18 issue