Only a couple decades ago, physicians and their patients faced many uncertainties when it came to hereditary health risks. Some diseases were clearly genetic, so even one diagnosis in a family set off alarm bells. But many cancer types, neurological illnesses and other disorders with potential genetic components were like wild cards for people who worried about their own future health when a family member got sick.

Even today, 18 years after scientists mapped the entire human genome, physicians may not have definitive answers, but they are increasingly able to help patients discern health risks with the aid of genetic testing. For patients such as Bridget O’Malley, the information revealed and interpreted by a genetic counselor could make the difference between a cancer diagnosis or avoiding certain types of cancer.

“Having an expert available who can explain the nuances of a genetic result in an objective, unbiased way is crucial,” said Timothy J. Eberlein, MD, director of the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. “It takes time and expertise to help patients understand risk calculations and the resulting options. The genetic counselors on staff with Siteman are important members of our multidisciplinary teams.”

Setting off the cascade

O’Malley first met Susan Jones, a certified genetic counselor, during a Zoom meeting with multiple family members concerned about possibly carrying a variant in the BRCA2 gene. A normal BRCA2 instructs cells to manufacture a protein needed for tumor suppression by repairing cellular DNA. BRCA2 variants disrupt the production of this protein, increasing the risk of breast, ovarian and prostate cancers as well as melanoma.

At 51, O’Malley had never been diagnosed with cancer — and she wanted to keep it that way. “My mom was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2015, when she was 75. It was very treatable, and at the time no one really thought about it being BRCA-related,” O’Malley said. But when her mother, Noreen Kelly, faced a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in late 2019, Kelly’s doctor noted her prior cancer history and suggested testing.

Jones often works with patients who seek testing, not just to understand why they developed cancer or other diseases, but for the sake of their families. “They want to know if their families need to be concerned,” she said. “When we’re looking for familial gene mutations, we hope individuals don’t have it, but if they do, most consider it better to know so they can do something about it.”

The results indicated that Kelly had a pathogenic BRCA2 variant. Awareness of that variant resulted in adjustments to Kelly’s cancer treatment because BRCA2-positive pancreatic cancer is more receptive to specific types of chemotherapy. Kelly, however, died Sept. 28, 2021.

Kelly had been deeply concerned about her six children, all of whom had a 50% chance of a BRCA2 variant. The decision for multiple family members to seek testing when a relative is found to have a variant is known as cascade genetic testing. “Mom wanted us to have knowledge so we can make good choices and take the best care of ourselves,” O’Malley said.

The advent of telemedicine has made it even more convenient for family members from anywhere in the country to gather together and access genetic counseling. Not all institutions offer this benefit, but Washington University has embraced it. “The first step is to talk about the testing itself and provide background on why specific genes affect cancer risk,” Jones said. “This first appointment is informational, and I make sure to address concerns and questions before making any decisions about testing.”

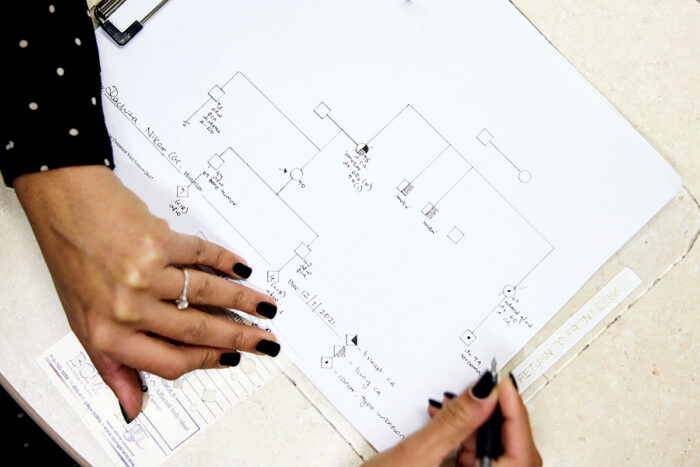

Based on the information an individual or family provides, Jones draws a three-generation family tree to illustrate risk and make sure the resulting testing panel covers all concerns. Family histories containing multiple cancer diagnoses may lead to a multi-gene panel. Jones provides testing kits to family members who want them. The tests, which use saliva samples, are mailed to a lab and offer the same accuracy as blood tests, with only about a 4% sample failure rate.

Jones pointed out that she and her colleagues always respect individual decisions regarding testing. “It’s a very personal decision,” she said. “We try to share in that decision-making process by offering the facts and discussing when or how a person wants that kind of information.”

O’Malley noted that not all her relatives were interested in testing. For instance, an older uncle who had no children decided against testing. However, several men in the family proceeded with testing for their own knowledge and to help inform their children of potential risk.

Providing the option to undergo genetic testing and having genetic counselors available to help families sort through the complicated physical and psychological issues was important to Patricia Dickson, MD, chief of the Division of Genetics and Genomics and the Centennial Professor of Pediatrics and professor of genetics. “When she was hired in 2018, she made it a part of her mission to bring cancer genetics back to Washington University and Siteman Cancer Center,” Jones said.

Eberlein, also the William K. Bixby Professor and Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Surgery, fully supported the decision. “Genetic counselors are the best people on the team to discuss all those complexities with the patient.”

By the time most people talk with Jones, they are seriously interested in pursuing genetic testing. Jones explains how testing helps determine treatments for existing cancers, what types of cancer could be associated with a variant and family risk levels.

“It’s important to spread the word among family members, but it can be difficult for a family member to know how to broach the subject and suggest a relative consider testing. We can help with that, too, to make the process less stressful,” Jones said. She offers template letters and emails, among other resources, that help explain the situation and urge relatives to talk with their doctors about testing.

Results point to options

Genetic test results do not mean a cancer diagnosis is imminent, which is one of the common fears that cause some people to avoid testing. Instead, uncovering a genetic variant means an individual’s risk for cancer is different than it would be without it. A risk analysis can direct patients to options for managing that risk.

Scientists are working to expand and enhance genetic testing abilities and resulting clinical decision making by sequencing hundreds of patients with colorectal cancer, multiple myeloma and cholangiocarcinoma, a rare bile duct cancer. Li Ding, PhD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Oncology and professor of genetics, is part of a research program known as the Washington University Participant Engagement and Cancer Genomic Sequencing Center, which received a $17 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. “The goal of our current study is to conduct large-scale genomic sequencing in people with these three types of cancer to create a broad data platform on which we can identify the best actionable events in the clinical setting,” she said.

By referencing more genomic data, genetic counselors can compare individual findings with a broader baseline to identify specific treatments known to be most effective in patients with similar genetic profiles. “Genetic counselors are an integral part of this work,” Ding said. “When we use this data to identify clinically relevant information, the counselors and clinicians are the people who will deliver that information to patients and help them understand it.

“In this way, scientists in the lab and genetic counselors and clinicians who work directly with patients are incredibly important to each other,” she added. “Genetic testing is already important for many kinds of cancer, and we believe the ability to use genetic information to make significant clinical decisions about more types of disease will increase greatly in coming years.”

Once results arrive, genetic counselors interpret and discuss them with patients such as O’Malley. In the case of BRCA2-positive women, Jones recommends appointments at the high-risk Gynecologic Oncology Clinic, where breast and ovarian cancer risks can be monitored on an ongoing basis. Specialists available to help patients at higher risk of breast cancer include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists and psychologists. BRCA2-positive patients also are advised to see a dermatologist due to their higher risk of melanoma, which is 3% to 5% compared to the average 1% to 2% lifetime risk. In all cases, the center’s collaborative multidisciplinary approach is a win-win for clinicians who can plan coordinated care and patients who receive a complete picture of their risk with the assurance that all aspects are being addressed.

“Finding out I was positive … I was just in shock,” O’Malley recalled. “I was upset, but not like I would be if I had a cancer diagnosis. It was more a question of, ‘Now what?’”

After receiving their results, O’Malley and her sister made an appointment with gynecologic oncology surgeon Andrea R. Hagemann, MD, as a result of Jones’ referral. An associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Hagemann said that knowledge of BRCA and other high-risk gene variants are essential when considering screening and surgical recommendations.

O’Malley opted to have her uterus, cervix, ovaries and fallopian tubes removed to mitigate her ovarian and fallopian tube cancer risk and undergo close breast surveillance via mammograms and breast MRIs. “It was a relatively easy decision to have a hysterectomy because I knew I wasn’t going to be having children,” she said.

A personal choice

Treatment is highly personalized to each patient’s risk level, stage of life and future goals. For example, some women may opt to keep their ovaries — to preserve fertility via egg harvesting or to prevent triggering premature menopause — and have only the fallopian tubes removed. Patients at menopausal age may prefer uterine removal to reduce endometrial and cervical cancer risk and help ease hormonal replacement management.

“We want patients to know that there are choices,” Hagemann said. “There’s not just one way to go if you have a BRCA2 mutation.

In the case of a BRCA2 mutation, some patients opt for both ovary removal and prophylactic double mastectomy with breast reconstruction. Because of Siteman’s multidisciplinary and collaborative approach, all of this can be performed in a single surgery, reducing exposure to anesthesia and other surgical risks. Many of the team’s specialists participate in expert panels that set and refine National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, and are uniquely suited to ensure that patients receive precision care, taking into account all factors.

O’Malley’s aunt, Julie Childress, who had a hysterectomy before learning she had the BRCA2 variant, chose not to have a mastectomy at this time. Instead, she is participating in more frequent screenings for breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and melanoma, which provide a sense of control regarding her health and future. “As hard as it was to hear this news, it’s been an impetus for me to be more vigilant about my health,” she said.

Screening is vitally important for early detection in many types of cancer. Ovarian cancer, however, often presents with subtle symptoms and is diagnosed at late, metastatic stages. This makes genetic testing all the more beneficial as it alerts practitioners and patients to risk probability before a diagnosis is made.

Up to 25% of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer are found to carry a high-risk mutation.“If we had known they had the variant, we potentially could have prevented that diagnosis by being proactive,” Hagemann said. Finding these mutations early and reducing risk via surgery after genetic counseling is still key for ovarian cancer prevention.

Certain cancer diagnoses automatically flag a referral for genetic counseling and testing. In particular, ovarian, pancreatic, metastatic prostate, colon and endometrial cancers are known to have possible genetic links. These cancers often involve point-of-care genetic testing and brief counseling in on-campus clinics at time of diagnosis and then a referral to further counseling with one of the certified genetic counselors when variants are found.

Women who have a strong family history of breast cancer, diagnosis before the age of 50, or have been diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer are also candidates for genetic testing. However, anyone with concerns about family health history can self-refer to Jones or her colleagues for consultation and testing. Jones notes that about half her patients are referred from oncologists and half from their primary-care physicians or via self-referral.

With the knowledge provided by the genetic information, patients can take important steps to enhance their health and reduce cancer risk via lifestyle changes and noninvasive treatments. Health preservation planning includes consideration of diet, exercise, stress management, screening schedules and preventive medications. For instance, those at higher risk of colon cancer could benefit from more frequent colonoscopies, which can prevent cancers by removing precancerous polyps.

Responding to increased demand

As more people realize the benefits of genetic testing, Washington University is poised to be on the forefront of ensuring testing is easily accessible. Eberlein saw demand increasing and knew the trend would continue, especially in the age of personalized medicine based on genetic information. “Nationally, the shortage of certified genetic counselors can increase patients’ wait time to get an appointment,” he noted. “And as clinicians, we also need genetic counselors on the patient care team because they provide a really important service to patients with complex medical histories and issues.”

One solution for Washington University and its associated clinical institutions was to establish a new 21-month master’s degree program in genetic counseling, which is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling. “Through this program, we’re helping to provide more certified genetic counselors, some of whom we hope will stay here and work with us,” Eberlein said.

Jones noted that she and her colleague, Rachita Nikam, stay busy with in-person and telehealth clinics, and added that working with Noreen Kelly and her family is an example of the ideal situation. “When a diagnosis and subsequent genetic test result lead to a family cascade so that many others can understand their risk and manage it for a healthier future, that’s exactly what we want — keeping people as safe and healthy as possible.”

Understanding cancer genetics

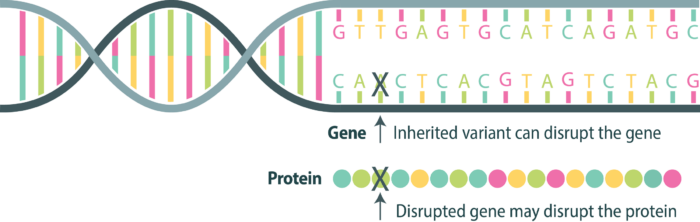

Genetic counselors help families navigate hereditary cancer risk, prevention and early detection. These diagrams are a sampling of what a counselor might share with patients to explain their genetic risk of developing cancer.

How gene variants cause cancer

BRCA1 and BRCA2 normally act as tumor suppressor genes, producing proteins that help repair damaged DNA. Inherited variants in these genes can prevent proteins from working properly, increasing the risk of several cancers.

Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis

Everyone has two copies of each gene — one copy inherited from each parent. For a protein to be disrupted and cause cancer, variants are needed in both genes. This is the principle behind Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis.

First hit Gene 1 – may be inherited

If a person is born with a pathogenic variant, this leaves only one gene producing the needed protein.

Second hit Gene 2– may be random

If the second gene is altered/mutated due to an environmental exposure or random event, now no protective protein is produced in the cell. This can allow cancer to begin.

Variant classification

A variant in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes doesn’t automatically mean cancer. There are thousands of known variants, which are classified based on their likelihood of pathogenicity.

Pathogenic or

likely pathogenic

Actionable variants. Recommendations can be made. Family members may be tested for their cancer risk.

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS)

Unknown variants. Not yet known to affect cancer risk. Still being researched. Will be reclassified later.

Likely benign

or benign

Harmless variants. Considered part of normal human variation.

Published in the Winter 2021-22 issue