In ordinary times, scientists and physicians spend months, or even years, working to secure funding for their research. When the novel coronavirus burst into world consciousness in early 2020 and rapidly became a global health concern, that timetable became untenable. By spring, School of Medicine investigators had quickly shifted gears to mount a coordinated response to the crisis. They needed an immediate infusion of capital to advance efforts that could save hundreds of thousands of lives.

To secure this capital, Chancellor Andrew D. Martin and Executive Vice Chancellor for Medical Affairs David H. Perlmutter, MD, formulated a bold plan: They would convene a group of dedicated supporters and community leaders, bring them together with experts leading the medical school’s pandemic response and invite them to invest in the work.

The group, dubbed the Coronavirus Research Task Force, had its first meeting April 16. Within days, members committed $2.5 million in seed funding. After additional meetings were held throughout the summer, the total climbed

to $4 million.

“These leaders’ generosity and confidence in our capacity to advance countermeasures against a serious infectious disease gave us a critical boost,” said Perlmutter, the George and Carol Bauer Dean of the School of Medicine. “Few academic medical centers in the country can count on such enthusiastic support.”

Here, Andrew M. Bursky, a university trustee who made two gifts to support COVID-19 research, and virologist Sean P. J. Whelan, PhD, the Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor of Microbiology, discuss their involvement with this unique funding mechanism — and its impact in the pandemic fight.

Can you describe your thoughts and experiences in the early days of the pandemic?

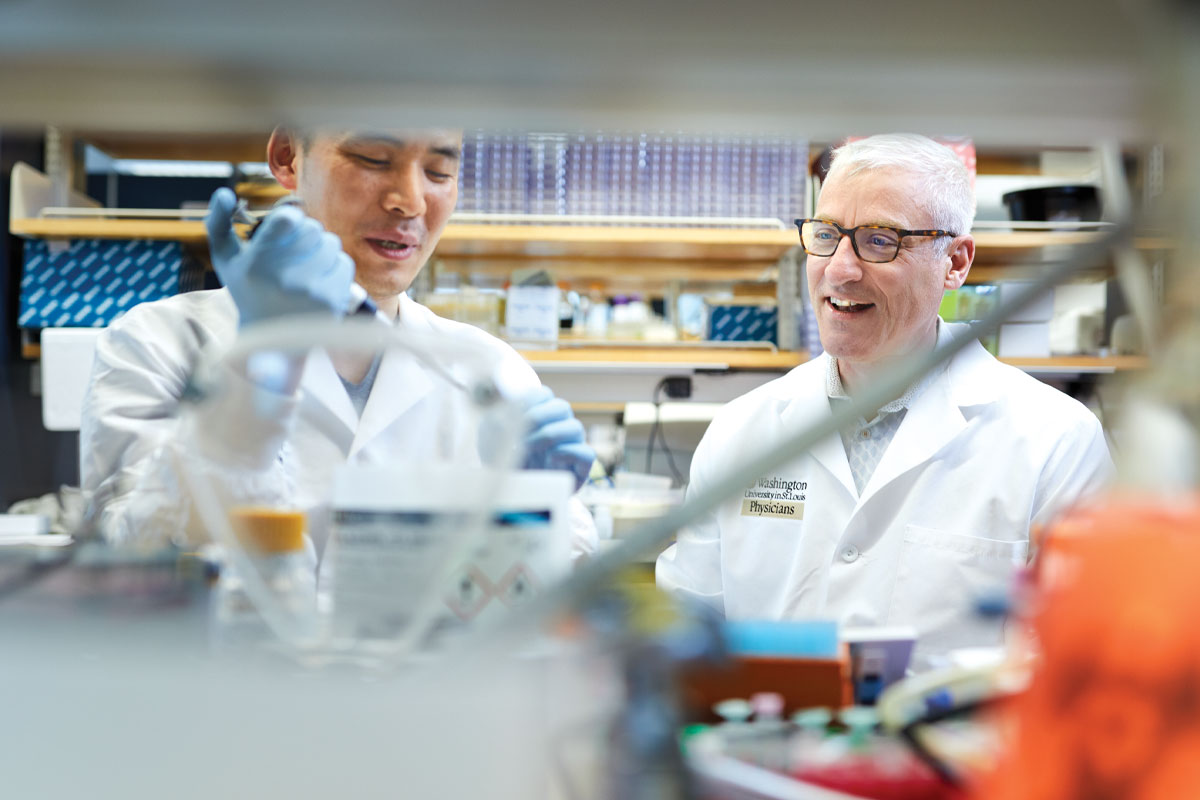

Whelan: When I arrived in St. Louis on Jan. 4, 2020, to begin my tenure as head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology, I planned to focus on recruiting new faculty members. I’d heard a little bit about SARS-CoV-2 in the news, and I thought it had real potential to be something concerning. Very early on, I met with Mike Diamond (WashU virologist and the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine), and we discussed our interest in investigating the virus. We started having weekly meetings with faculty members who were working with COVID — people from all over the university. It was a way for information to be rapidly exchanged among different groups. At the time, my lab was in the process of moving here. It finally arrived during the first week of March, and by then, we knew the virus was widespread and could not be contained through public health measures alone.

Bursky: When the country started shutting down in March 2020, it was an instantaneous shock. Suddenly, the world changed almost beyond recognition. It was destabilizing. My work as chairman of an equity investment firm involves identifying and fixing businesses that have lost their way. So in a weird way, I was accustomed to being in destabilized environments. That said, the pandemic affected all of us personally. We shared the real human fear that something terrible could happen to people we cared about.

What obstacles did WashU researchers face in securing funding to conduct COVID-19 research?

Whelan: In the beginning, most of us were working without financial support. Fortunately, WashU had given me some funds for my lab as part of my recruitment package. I used that and some departmental resources to outfit a Biosafety Level-3 containment laboratory by the end of January. And that was the only place anyone was working with the virus for a while. We were trying to get federal grants to support COVID-19 research at the medical school. But obtaining funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a slow process. It takes months. In fact, I was notified that I received my first COVID-19 grant more than a year into the pandemic.

What did you think about the idea of convening a task force to solicit funding from donors?

Bursky: When I heard about the plan from Chancellor Martin and Dean Perlmutter, I was excited to participate. And I thought there were many others like me who would be eager to join. When you fund medical research, as my wife, Jane, and I have done for many years at Washington University and elsewhere, you resign yourself to the fact that it may take a decade to see results. With this COVID-19 research, it was exhilarating and encouraging to think it could have an immediate impact.

Whelan: It was exhilarating and encouraging for me as a scientist, too. In the task force meetings, my colleagues and I were able to interact directly with people who’d been successful in the business world, and they didn’t want to deal with the level of bureaucracy that is associated with the grant-funding process. They wanted to know, “How do we get something done now?” It was impressive to see these business leaders and donors come together so quickly and recognize the importance of our research.

How did the seed funding from donors change the way researchers approached their work?

Whelan: It allowed us to focus on science instead of applying for grants. Their support was incredibly valuable to my lab and to many other labs in the WUSM community, such as those led by Mike Diamond, Daved Fremont, Ali Ellebedy, Rachel Presti, Jeff Milbrandt (McDonnell Genome Institute) and Debbie Lenschow. It helped us advance two vaccine candidates, one of which is now in clinical trials, an early mouse model to study infection, and a Biosafety Level-2 high-throughput assay to investigate neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Funds also were allocated to support the development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and a rapid COVID-19 saliva test that played an important role in combating the pandemic at the university and in our community. All of this work and more was happening simultaneously last summer.

Were you surprised that task force members provided a significant amount of funding so quickly?

Whelan: I was at the time. But looking back, I’m less surprised. It was clear the potential impact of the pandemic was huge. During one of the group’s meetings, we discussed the financial costs, how much money was being lost every day because of the effects on the economy. I remember one task force member said that if we didn’t have immediate action, there wouldn’t be an economy.

Bursky: It wasn’t surprising to me. All the task force members are familiar with the intellectual horsepower of our medical school faculty. And we were excited to hear what they were focusing on. The breadth of it, from testing to therapeutics to vaccines, was very encouraging. It was a privilege to be able to participate in something like this. And I don’t think our contributions are unique. We represent a small subset of a very large group of folks who for many years have given to this institution. I suspect I speak for all task force members when I say it was rewarding for us to have had an impact, in some small way, through the talent and genius of these researchers.

How unusual is it for an academic medical school to ask investors to fund research this way?

Whelan: To have people committed and engaged and willing to fund the science you are doing in real time — that’s never happened to me before in my career.

Bursky: I think it was the only way to approach it. And I give David Perlmutter and Andrew Martin credit for having that insight. It was an act of courage for them to step out and ask for multiple millions of dollars with nothing more than some good ideas and preliminary data. But the truth is, it wasn’t that difficult to get to yes. My peers and I are accustomed to investing in the person, the entrepreneur, as much as the idea. And that’s exactly what happened here, at least for me. I have such a high regard for these researchers, just as I have for the people I invest in on the commercial side. You bet on proven talent that has historically delivered the goods. And in this case, I don’t think anyone was disappointed with the outcome.

What is it about Washington University that makes it possible for people to come together to address our world’s greatest challenges?

Bursky: A key WashU characteristic, which I think had an impact on the success of these COVID efforts, is the ingrained, almost genetically programmed, collaborative nature of the institution. People here are wired to collaborate.

Whelan: The very first paper that came out of my lab after I moved to WashU, which describes a virus we generated and our Biosafety Level-2 assay that mimicked the neutralization of COVID, involved seven principal investigators here. And it was published in June 2020. The speed with which it came together reflects a tremendous amount of cooperative effort.

The collaboration really is unparalleled. And I think it’s a testament to this community.

Coronavirus Research Task Force members

Andrew M. Bursky*

Alumnus, trustee

Sam Fox*

Alumnus, emeritus trustee

David W. Kemper*

Distinguished trustee

James S. McDonnell III*

School of Medicine National Council member

John F. McDonnell*

Alumnus, emeritus trustee

Jim McKelvey*

Alumnus, trustee

Philip Needleman, PhD*

Former faculty member, emeritus trustee,

School of Medicine National Council member

Michael Neidorff*

Andrew E. Newman*

Distinguished trustee,

School of Medicine National Council member

Mike Powell

Trustee

Rodger O. Riney

School of Medicine National Council member

Jim Weddle

Alumnus

Jess Yawitz, PhD*

Alumnus, former faculty member

*Donors

Faculty presenters

Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD

Herbert S. Gasser Professor

Ali Ellebedy, PhD

Associate professor of pathology & immunology, of medicine and of molecular microbiology

Jeffrey D. Milbrandt, MD, PhD

James S. McDonnell Professor of Genetics, head of genetics

William G. Powderly, MD

Dr. J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine, Larry J. Shapiro Director of the Institute for Public Health

Rachel M. Presti, MD, PhD

Associate professor of medicine

Sean P. J. Whelan, PhD

Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor of Microbiology, head of molecular microbiology

Published in the Autumn 2021 issue