Changing the world starts right here in the place we call home. Siteman Cancer Center, with the support of WashU Medicine physicians and BJC HealthCare, is working to reduce the barriers to cancer screening, and improve prevention and access to care by listening to, visiting and serving underserved communities across the St. Louis region.

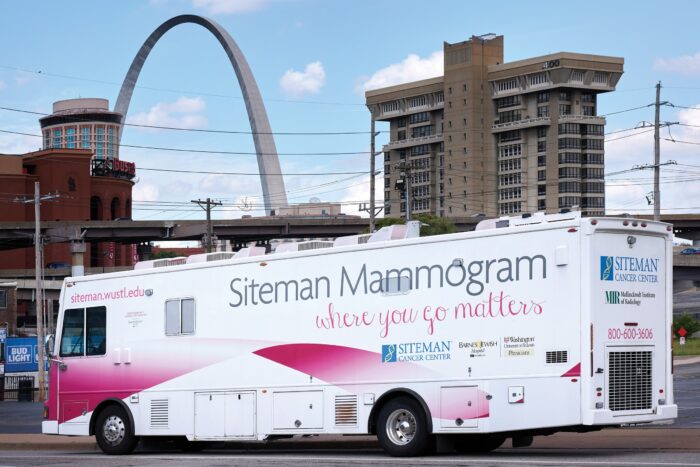

From inflatable colons to mobile mammograms, these efforts focus on outreach and screening in 82 counties with high cancer rates in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois. Combined with the research being done at WashU Medicine and the clinical trials being conducted at Siteman, the communities in and around St. Louis are often among the first to experience breakthrough experimental treatments aimed at saving lives around the world.

Our mission is simple: to improve access and health outcomes for all, making a lasting impact on the lives we touch here at home and beyond.

“It takes multiple partners to actually get to a community that has historically been isolated and medically underserved to increase both the awareness and understanding of the value of screening, and then link that community to services if screening tests indicate further care is needed.”

— Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH, the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery; director of the Public Health Sciences Division in the Department of Surgery; and associate director of prevention and control at Siteman Cancer Center

Meeting communities where they are

Jean Wang, MD, PhD, a WashU Medicine professor of medicine and of surgery, smiles as a small crowd gathers and she invites them to “step into the colon.” She is standing beside a huge, inflatable colon — a walk-through tunnel that gives people an inside look at colon cancers, polyps and healthy tissue. It’s hard to miss at the health fair, where Wang uses it to bring people in to answer questions and share information about the signs and symptoms of colon cancer.

Wang and many WashU Medicine physicians and researchers at Siteman Cancer Center spend a portion of their time outside the boundaries of their clinics and labs to bring cancer prevention and detection resources to the public, especially those in medically underserved communities.

Leading these efforts for Siteman Cancer Center is Bettina Drake, PhD, WashU Medicine professor of surgery and associate director of community outreach and engagement at Siteman. “This is a team effort that requires people from multiple backgrounds across WashU Medicine and Siteman in order to conduct outreach and engagement that truly creates change and promotes health equity — to collaborate in a way where we’re working with the community and hearing their needs so we can implement sustained efforts that have a meaningful impact,” she said. “It’s not something that anyone can do alone.”

Through Drake’s passionate leadership, Siteman, together with WashU Medicine and BJC HealthCare, recognizes that it’s not enough to only offer patients the most advanced therapies and conduct innovative research aimed at developing tomorrow’s treatments today. Caring for the community as a whole and preventing cancer from developing in the first place is also a critical part of their efforts. Much of this work is led by Siteman, with a particular focus on community outreach and screening efforts in 82 counties in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois that have some of the highest incidences of cancer, including breast, colon, prostate and lung.

COMMUNITY IMPACT

200,000 preventive screenings performed in 2023

And they’re seeing promising results.

For instance, colorectal cancer rates have decreased by 30% in rural Missouri, and late-stage breast cancer diagnoses have decreased by 33% among Black women in north St. Louis County and by 31% in St. Louis following the advent of outreach programs targeted to those areas, including churches, The Breakfast Club, The Empowerment Network and the Urban League. A closer look at such programs reveals how they benefit the public and physicians alike.

PECaD focuses on those most in need

Community outreach and cancer prevention efforts such as Wang’s are part of the Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities (PECaD). The program embodies the power of collaboration between WashU Medicine, BJC HealthCare and Siteman in providing innovative cancer care based on the latest research, and an ongoing, deep commitment to the health of our region.

As associate director of prevention and control at Siteman, Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH, the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery and director of the Public Health Sciences Division in the Department of Surgery, applies the experience that has garnered him an international reputation as a pre-eminent cancer prevention researcher, to the center’s outreach and prevention efforts. “It takes multiple partners to actually get to a community that has historically been isolated and medically underserved and increase both the awareness and understanding of the value of screening, and then link community members to services if screening tests indicate further care is needed,” said Colditz. “That’s been a fairly big part of our response. Rather than saying, ‘Well, we’ll just do some outreach and education and hope it works,’ we’re trying to fill in gaps wherever they arise and make a real difference in these communities we serve.”

WashU Medicine physicians working with PECaD are educating and screening individuals for colorectal, lung, prostate and breast cancers, often collaborating with community and government organizations and research programs. For instance, PECaD’s lung cancer screening initiative receives funding from the Veterans Administration. “Not everyone can get to a rural VA clinic, and veterans’ partners may not qualify for VA coverage. So how do we actually capitalize on the opportunity to get them to show up for a screening?” Colditz asked.

“Rather than saying, ‘Well, we’ll just do some outreach and education and hope it works,’ we’re trying to fill in gaps wherever they arise and make a real difference in these communities we serve.”

— Graham Colditz, MD, DrPH

“Wouldn’t it be cool if we could suggest veterans and their dependents could get screened, and show them the places that we can help them get access?” he continued. “This kind of effort really underlines the value of partnering and finding those opportunities, and there’s a concerted effort to do that across our programs.”

In another example, Michelle Silver, PhD, an assistant professor of surgery, is working to increase awareness of HPV vaccines among rural populations to help prevent cervical cancer. Her work evaluates access and informs people of vaccine availability through rural pharmacies in order to increase vaccination rates in these often medically underserved areas.

COMMUNITY IMPACT

20 Missouri counties removed from list of colorectal cancer hot spots

“It’s almost embarrassing that we — as a country — are at the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, and challenges of access exist to cancer screening services that half the population takes for granted,” Colditz noted. Through the various programs under the PECaD umbrella, WashU Medicine researchers and physicians are learning more about barriers that keep people from seeking out cancer screenings, such as distance from cancer screening services and a lack of transportation, job insecurity, cost and lack of health insurance and cultural influences.

“From the patient to the community health worker to the provider to the health system, our leaders collaborate in a way where we’re hearing the needs and we’re implementing sustainable efforts to promote change,” said Drake.

This commitment to learning and understanding is echoed by Aimee James, PhD, a WashU Medicine professor of surgery in the surgery department’s Public Health Sciences Division and co-leader of the prevention and control program at Siteman.

“We can go to the literature to know how screening works in theory, but it is critical to go and learn from the people, how it works for them, what the patient and provider challenges are.”

Bringing screenings to the people

In collaboration with Siteman, WashU Medicine physicians and researchers are taking important messages to both inner city and rural populations while learning more about population-based and individual barriers to screenings. This two-way communication means that the public benefits from cancer screenings, while WashU Medicine faculty gain insights that then inform their teaching and research focus.

Wang, the inflatable-colon tour guide, invites health fair visitors to take home free FIT kits — fecal immunochemical test kits — for colorectal cancer screening. The colorectal cancer screening kits allow individuals to take a stool sample and send it to a BJC HealthCare lab for a free analysis, where Wang personally reviews each result.

Community Impact

31% in St. Louis and 33% in St. Louis County breast cancer mortality reduction in Black St. Louis patients over eight years

With an expansion of the program, FIT kits will be available through the Siteman mobile mammography unit that visits area grocery stores and similar locations. Even people who do not receive mammograms can take home a FIT kit to screen for colorectal cancer.

Community outreach to raise awareness about breast cancer is another area of focus. Katherine N. Weilbaecher, MD, the Oliver M. Langenberg Distinguished Professor of the Science and Practice of Medicine, a professor of medicine and co-leader of the Breast Cancer Research Program at Siteman, specializes in treating metastatic breast cancer and is determined to make mammograms less daunting so more women will get screened.

“Over the years, I’ve seen higher numbers of African Americans being diagnosed with advanced breast cancer, and when I look at the data that’s coming from my own backyard, there are higher mortality rates in north St. Louis County than in other areas of the St. Louis region,” she said. Weilbaecher finds this frustrating, considering that when breast cancer is diagnosed early, it is highly treatable and the five-year survival rate is almost 100%. Working together with PECaD, she joined other colleagues across WashU Medicine to address this troubling trend.

The mobile mammography unit became a crucial part of efforts to increase awareness and bring screening technology directly to neighborhoods where individuals are less likely to seek out cancer screenings. Then, working with colleagues at Christian Hospital and Northwest HealthCare, located in the areas of greatest need, Weilbaecher began to explore how to make it easier for patients to return for follow-up exams when a mammogram indicates an abnormality.

The outcome was a mammography clinic located at Siteman’s north St. Louis County location, where results are provided and follow-up exams are scheduled before the patient leaves. The idea is to prevent patients from falling through the cracks between an abnormal screening exam and follow-up.

Weilbaecher also walks the walk, getting her own screening mammograms at the Northwest HealthCare facility and works to make the experience less fraught. “We want to make this a positive experience for women,” she said.

Besides the actual screening options, women in north St. Louis County are getting information about the importance of mammograms from an unexpected source — their daughters. Lannis Hall, MD, WashU Medicine associate professor of clinical radiation oncology and PECaD’s clinical trials leader, is taking the message to Hazelwood School District high school students and encouraging them to “Tell Your Momma.” Students learn about breast cancer risk factors, screening guidelines and the importance of family history and healthy lifestyle habits.

Making the program fun by incorporating healthy activities and friendly competitions brings the message home, and providing students with a QR code that links to breast health information makes it more easily accessible.

“This partnership is unique in its goal to empower young ladies, many of whom are at high risk, to become knowledgeable about healthy lifestyle changes early in life. Their role in educating their mothers and loved ones about these changes is crucial and can positively influence screening and lifestyle behavior,” Hall said. “The program encourages this education from daughters to mothers and loved ones, emphasizing that breast health is a family affair.”

Collaborative efforts extend across the region

WashU Medicine physicians who work with community groups also collaborate with colleagues across Missouri, Illinois and the nation. For example, Wang’s efforts to increase colorectal cancer screening and prevent new cancer cases are known throughout the state in her roles as a co-founder and past chairwoman of the Missouri Colorectal Cancer Roundtable and executive committee member of the Missouri Cancer Consortium.

Wang said the roundtable, established in 2018, is “a group that brings together all the different organizations throughout the state of Missouri that are interested in improving colon cancer screening, access and prevention.” The roundtable allows her to work with the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services and various nonprofit and patient advocacy organizations.

These types of collaborative opportunities benefit both patients and physicians. As organizations receive information and guidance from WashU Medicine physicians, the physicians themselves discover new ways to bring health care to the public, an important aspect of their roles as clinicians.

Other physicians, including Hall and Weilbaecher, communicate with peers across the region, participating in consortiums, conferences, panels and committees. “Right now, I’m seeing a lot of collaboration,” Drake said. “There’s genuine interest across the board, beyond the borders of our campus.”

A win-win

The WashU Medicine physicians working in community-facing programs agree that medically underserved communities and demographic groups benefit from face-to-face interaction in a neutral location where they can learn about what screenings and diagnostic tests they qualify for and better understand what resources exist to support their health. Many of these patients were historically considered “noncompliant,” when in truth they were experiencing barriers that the medical establishment needed to better understand.

“Going out in the community definitely helps you to connect with the patients better,” Wang said. “I’ve been to churches in North County, spoken there, and attended health fairs. And to be in the church, in the community, it’s just a completely different way of connecting with patients compared to the clinic.”

“I’m an oncologist, and I would love to put myself out of business because women understand how to get screened and diagnosed early and how to live a healthy lifestyle that lowers their risk of breast cancer,” Weilbaecher added.

Drake is equally enthusiastic about the benefits of community outreach. “We’re really focused on hearing from the community, what their needs are, and bringing that back to clinicians and researchers,” she said. “And we’re also learning about new services that are available within the clinics and systems and getting that information out to the community so that everyone is aware of what’s available. Together, we are working to improve access and the health of everyone across the board.”

We don’t yet know what the next community-changing program will be, but we know where it will start—with generous supporters who invest in furthering cancer education and prevention. Make a meaningful difference by giving to support cancer research.

Published in the Autumn 2024 issue