The virus had not yet left Wuhan, China, when the School of Medicine, Barnes-Jewish Hospital and BJC HealthCare started bracing for a medical disaster of greater magnitude than any they had ever experienced. Six weeks before COVID-19 reached St. Louis, incident command centers were set up at every BJC hospital, with a joint incident command center for the medical school and Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Employees representing every key operational function reported to the command centers at dawn. They showed the guards their badges, had their temperatures checked, sanitized their hands, wiped down their laptops — then looked up. One long wall was covered with monitors: news bulletins; the hospital’s census; global epidemiological charts and maps, regional stats. As information was processed and key decisions made, word shot out to the hospitals, where health-care workers adjusted instantly to changes in safety or treatment protocols.

The collaboration was unprecedented.

“We all had a common enemy, and that enemy was lethal and creative.”

— John Lynch, MD, president of Barnes-Jewish Hospital and professor of medicine

Vital communication

Information was changing hourly. Communication leaders at WashU Medicine and at Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals swiftly partnered on messaging to keep vast institutions, multiple sites and experts across many disciplines in sync. At the medical school, Associate Vice Chancellor Joni Westerhouse channeled news to Medical Public Affairs, which disseminated info via a COVID-19 newsletter and website, press releases, social media, podcasts and video.

Foresight

Two years earlier, foresight had driven the purchase of emergency operations software. “We could send alerts, share information, and customize the platform to gather specific data — what critical supplies did we need, how do we get out in front of this?” said Ryan Nicholls, assistant director of emergency management. The incident command center went virtual as soon as it could: “Critical people were making critical decisions,

and we could not risk them getting sick,” he said.

Joining forces

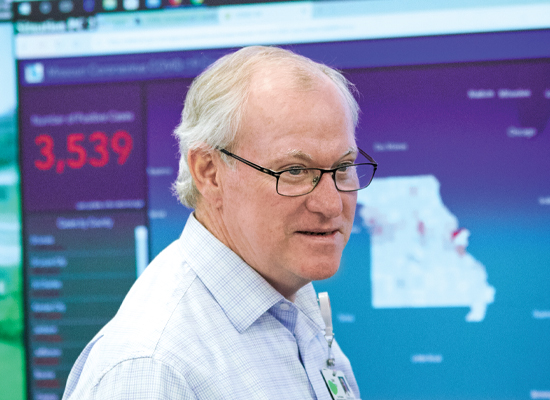

In February 2020, Medical Campus leadership contacted Alex Garza, MD, chief medical officer of SSM Health, suggesting that the three big regional systems — SSM, Mercy, and BJC — get together. “Very quickly after that, we started a dialog with local elected officials and their public health directors about a collective response to the pandemic,” said Clay Dunagan, MD, BJC’s senior vice president and chief clinical officer and professor of infectious disease.

Massive operational shifts

The incident command center conducted briefings each morning and throughout the day and did wrap-ups in the evenings, with some staffers invariably spending the night to keep trying to find N95 respirators or sterile gowns.

David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the medical school, convened with all department heads and BJC leadership regularly on Zoom, as did many other groups. Infectious diseases clinicians and COVID-19 researchers exchanged information about what was happening at the bedside and about possible diagnostics and treatments being developed in the lab. The Department of Medicine set up a weekly grand rounds series viewed by thousands, offering updates on COVID-19 management and care. And intensivists met for 90 minutes daily with an array of specialists, discussing the intricacies of care for an illness that could attack multiple organ systems.

“There was no playbook for this. We had to create an organizational structure. Get the hospital ready for a surge. Figure out how to protect everybody, how to handle telemedicine. Move faculty and staff to remote operations and put classes online. Stop nearly all research and shift the focus to coronavirus.”

— David H. Perlmutter, MD, dean of the School of Medicine

Going virtual

At the first sign of community spread in mid-March, nonessential employees began working from home and medical school classes went online. Fourth-year students were nearly finished, said Eva Aagaard, MD, senior associate dean and the Carol B. and Jerome T. Loeb Professor of Medical Education. “Their disappointment was missing Match Day — a really strong tradition for us — and graduation, both of which were virtual.”

Stopping research midstream

For safety purposes, the only research projects to continue were those involving rare and irreplaceable samples or months of work that would be undone by stopping. That research was deemed “essential,” as was all COVID-19 research. Though shutting down labs was painstaking and laced with disappointment, Jennifer Lodge, PhD, vice chancellor for research, was relieved to see “so much cooperation, so many people wanting to do the right thing.” Lodge, also a professor of molecular microbiology, consulted with colleagues at Stanford, Harvard and Columbia, learned best practices from WashU infectious disease experts and set up committees to plan, document and color-code. All the faculty wrote plans for shutting down and reopening labs.

PPE shortages

“Our typical distributor was out of everything, so we had to open up new supply lines. We do have a relationship with a group in China — we were helping them build an oncology hospital — so they would send us supplies monthly,” said Paul Scheel, MD, MBA, associate vice chancellor for clinical affairs and CEO of Washington University Physicians. “Sometimes, the U.S. government would confiscate them at customs and divert them to areas of higher need, so we had no idea what we would have at any given time.”

Meeting the challenge

Experts in different disciplines braided and rebraided, forming small work groups to solve problems. Clinical staff were surveyed to see who would be available to pinch hit if, for example, BJH ran out of nurses or the COVID-19 ICUs needed more physicians.

“Some people slept here in the dorms for weeks on end,” Scheel said. “It was all hands on deck.” A Coping With COVID-19 hotline facilitated by the Department of Psychiatry offered in-the-moment therapy for essential workers, and Human Resources rolled out a wealth of support resources to the entire WashU community as it adjusted to the pandemic. As the COVID-19 census rose, supervised medical residents provided the majority of care for patients who didn’t have the virus.

Social distancing does not come naturally in health care, where people work side by side, confer in discreet murmurs in the hallway and support each other. Yet “we had remarkably few workers who became positive,” said William Powderly, MD, FRCPI, director of the Institute for Public Health, “and the majority of those who did acquired the infection in the community.”

“We had to change our questions — not ‘Do you feel sick?’ but ‘Do you have a fever?’ — because health-care workers are soldiers.”

— Jennie H. Kwon, DO, MSCI, associate hospital epidemiologist, on tracing exposures

Testing breakthrough

From the outset of the pandemic, clinicians and researchers began looking for an alternative to nasal testing, which requires reagents and special swabs that were in short supply nationally. “One of Dr. Perlmutter’s early charges was to develop novel testing,” said Paul Scheel, CEO of Washington University Physicians. The McDonnell Genome Institute promptly developed a rapid, accurate saliva test. The test was used to physically reopen the Danforth Campus in September, and Missouri’s governor worked to make it available across the state.

Infection control

While the COVID-19 care providers fought the virus, their colleagues kept it from spreading through the hospital. A team co-led by epidemiologist Jennie Kwon and infectious diseases specialist Hilary M. Babcock, MD, MPH, built a system to trace contacts among patients and employees and monitor and assess changes. A COVID-19 call center also opened to evaluate symptoms of WashU and BJC employees and checkpoints were established to screen everyone entering the campus. To check temperatures, Scheel realized the perfect solution would be the thermal cameras used to screen people at airports.

Advising the region

With CDC guidance limited and changing, infectious disease docs worked even harder to inform the public — doing a raft of media interviews and helping St. Louis strategize closing and reopening. The infectious diseases division provided the state of Missouri with data analysis, modeling and research. Between the Institute for Informatics at the School of Medicine and the health-care informatics at BJC, physicians and civic leaders were able to see where admissions were occurring, to understand who was at higher risk for hospital admission or critical care and to predict surges. That level of analysis was not available in many parts of the country. “Our position in this community and the expertise we bring to the table mean that the work we do reverberates far beyond our walls,” Dean David Perlmutter said.

Moving forward

Rather than be paralyzed by this crisis, “we used it,” said Victoria Fraser, MD, the Adolphus Busch Professor of Medicine and head of that department. “People had been slowly working on online education and telehealth for years, and because of COVID-19, we started them up in a couple weeks.” It also took only two weeks to stand up the new respiratory clinic, an endeavor so complicated it would normally involve years of planning.

“In our normal way of working together, we work until we get it exactly right,” BJH President John Lynch observed. “Perfectionism runs rampant on both sides of Euclid Avenue. It makes us great institutions, but it doesn’t make us nimble.

“There is a sense now that together, BJH, BJC and WashU can solve problems of a magnitude we had never actually even contemplated,” he said. “That we can take on challenges so big they weren’t even imaginable.”

“The pandemic has pushed the genius of human innovation to move more quickly to do things that sometimes we prohibit by regulation and hesitancy.”

— Brent Ruoff, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine

Changes in health care

“Telehealth for sure is here to stay,” said Victoria Fraser, head of medicine, “particularly for vulnerable patients who live at a great distance or have trouble with mobility.” The necessity of infectious disease specialists is newly realized, said public health institute director Bill Powderly, adding that “over half of U.S. hospitals don’t have an ID specialist.”

Readiness for tomorrow

“The way we used the Joint Incident Command Center will help us solve future problems,” Lynch said. “It will be incredibly helpful to have the centralized ability to move staff where they are needed and balance our patient volumes across our campus and throughout our health-care system. It was amazing to watch the School of Medicine point its considerable resources at COVID-19 and develop its own COVID-19 test within weeks, then bring on an instrument that could do 1,000 tests a day!” The medical center now has stockpiles of emergency supplies that are expected to last many months. “We have learned how to manage thru COVID-19,” Scheel said.

Published in the Winter 2020-21 issue