Editor’s note: Writer Tamara Bhandari and photographer Matt Miller traveled to Guatemala to report on this story prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. INCAN has continued treating patients throughout the pandemic, despite a nationwide nightly curfew and a lack of bus service that makes the daily trips to the clinic challenging for patients and staff. More than 300 patients were treated on the new Halcyon machine in its first year of operation. For about four months in the summer and fall of 2020, one of INCAN’s other radiotherapy machines was out of commission and another was only partially functional. Without the Halcyon, INCAN’s doctors would have had to refuse or delay care for dozens of cancer patients. Since this story was written, Alejandro Marroquin died of his disease.

Nellida Yesenia Castellanos rises before dawn every day to catch a bus that will take her through the crowded streets of Guatemala City to Instituto Nacional de Cáncerologia (INCAN; National Cancer Institute). As the bus drops her off, vendors who will spend their day hawking clothes, snacks and cheap plastic trinkets are setting up their street-side stalls.

The 45-year-old mother of three is undergoing treatment for colon cancer. When Yesenia Castellanos arrives at the institute, rows of plastic chairs already are filling up with patients waiting quietly under shrines to La Virgen de Guadalupe. Here, patients are treated on a first-come, first-served basis.

But on this November morning, Yesenia Castellanos doesn’t claim a plastic chair. Instead, she joins hospital staff, local dignitaries and foreign visitors in the auditorium. The group is celebrating the launch of a multimillion-dollar radiation therapy machine that will enable the institute to treat more people more effectively with fewer side effects.

The machine is the product of a years-long binational collaboration between Washington University, INCAN and Liga Nacional contra el Cáncer (National League Against Cancer), a nonprofit group that founded and continues to support INCAN. Yesenia Castellanos is there to speak to the experience of INCAN’s patients.

Yesenia Castellanos’ husband, Fidel Fernando Hernández, watches his wife address the gathering. He accompanies her to the hospital daily, a commitment that required him to take a leave of absence from his job at a local church. To pay for her treatment, the couple took out a loan nearly equivalent to a year’s salary. Increasingly, it is difficult to make ends meet. “I couldn’t let her do it alone,” he said through a translator. “She is my wife. We are in this together.”

The ceremony ends and the assembled VIPs troop off to admire the machine. It is something of a miracle that the machine is here. The initiative to obtain it nearly died and was revived so many times that it got dubbed “the zombie project.”

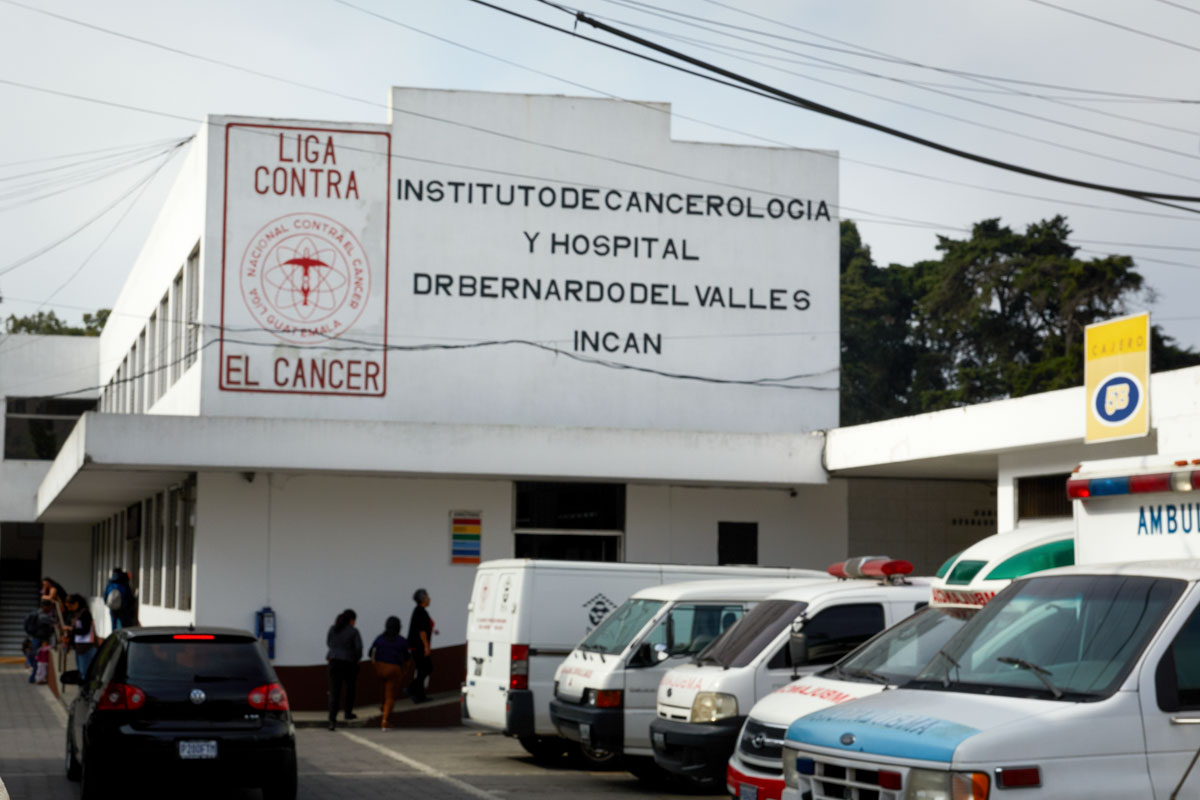

The only cancer clinic for the poor

In a country of 17 million where cancer is the third leading cause of death, only INCAN treats the poor. Patients arrive at the institute from all over the country, and those from far-flung areas can stay for free in a league-provided two-room hostel. Every afternoon, a hospital official enters the waiting room and calls loudly for anyone who needs housing that night to sign up. The 20 beds — in the form of five tightly-packed bunk beds per room — always fill up quickly.

The government subsidizes the majority of INCAN’s patients, two-thirds of whom are women. The lopsided gender ratio probably does not indicate that women develop cancer more frequently than men but rather that men delay seeking medical care until their symptoms are pronounced, said Angel Velarde, MD, INCAN’s research director. Delayed cancer detection is

a huge problem in Guatemala. More than 70% of INCAN’s patients are diagnosed with advanced disease.

Washington University has had a relationship with INCAN since 2010, when Graham Colditz, MD, DrPH, the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery, coordinated a yearlong, NIH-funded program to train local researchers to gather country-specific data that could be used to improve early cancer detection, prevention and treatment.

In resource-limited settings, radiation therapy is often the best cancer treatment option. It has high start-up expenses — radiotherapy machines cost over a million dollars and usage requires highly-trained personnel — but once a radiotherapy program is established, the cost per patient is a fraction of chemotherapy or surgery.

INCAN’s radiation therapy department was established in 1985, and these days medical staff treat 2,100 patients a year. The league bought two modern radiotherapy machines for the hospital in 2014, but neither is well-suited for cervical or breast cancer, the two most common cancers seen at the institute. And even working at full capacity, the two machines can’t treat everyone who needs radiation therapy.

Until 2019, the institute also had an old cobalt-based system, which still was being used well past its recommended lifespan. As such machines age, the radiation they emit weakens and it takes longer to treat each patient. A treatment that once took 10 minutes eventually took an hour.

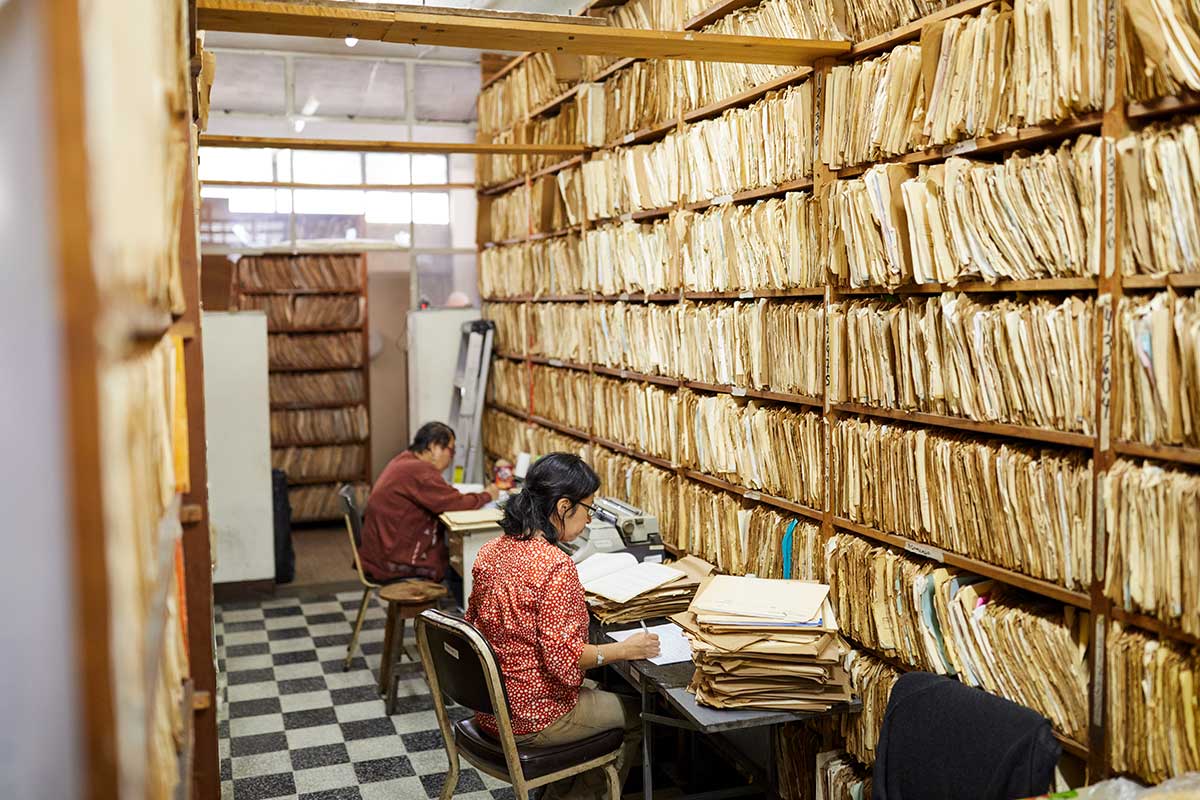

Kirk Douglas Najera — yes, named after the actor — is INCAN’s chief medical physicist and one of only a handful of medical physicists in Guatemala. Najera is responsible for designing each patient’s treatment plan, a job he performs every day in the face of immense challenges. The institute’s CT scanner — needed to map the outlines of tumors so radiation can be precisely targeted to minimize collateral damage — doesn’t always work. INCAN’s outdated computers can’t handle modern radiation-mapping software so much of the planning is done with decades-old software, and its patient files are still kept in manila folders.

In 2015, radiation oncologist Hiram Gay, MD, and medical physicist José García Ramírez — both members of the radiation oncology faculty at Washington University and native Spanish speakers — visited INCAN to assess the needs of its radiation oncology department. Among other things, Gay and García recommended upgrading the treatment-planning hardware and software and a radiotherapy machine.

But there was no money. The report was shelved.

An unexpected funding source

The plans to upgrade INCAN’s radiotherapy program lay dormant until late 2016, when William G. Powderly, MD, the J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine and the Larry Shapiro Director of Washington University’s Institute for Public Health (IPH), and Jonathan Green, MD, then the associate director of IPH’s Global Health Center, came across a call for applications from American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA), an office of the U.S. Agency for International Development.

It would be a big ask — the planners would need the maximum award amount, $2 million — but a new machine could enable INCAN to provide top-quality care, equivalent to what cancer patients receive in the U.S., to hundreds more people every year. Every year people die on the institute’s waiting lists.

An international team — including Najera, two INCAN doctors, Jacaranda van Rheenen, PhD, manager of the Global Health Center at the IPH, and others from IPH and the university’s radiation oncology department — set to work preparing the application.

Sasa Mutic, PhD, then the Endowed Professor of Medical Physics and professor of radiation oncology and now the senior vice president for Varian Medical Systems, suggested that they purchase the company’s Halcyon system. The Halcyon offers advanced treatments for the cancers most common at the institute, including cervical, lung, prostate, breast and head and neck cancer. In addition, it only requires the technician to take nine steps from the start to the end of treatment, compared with about 30 steps with older technologies.

The application was filed in April 2017. That same month, the Trump administration announced that it was freezing $450 million worth of aid to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador in an attempt to reduce the numbers of Central American migrants at the U.S. southern border. In two countries, team members waited, uncertain whether their project had been disqualified by the freeze.

More than a year later, they were notified their application had been approved, but with a change no one had expected: ASHA was prepared to give them $500,000. “The project nearly died,” Mutic said. “You can’t buy a quarter of a machine.”

The zombie project

On a conference call in summer 2018, the team discussed its options. Varian had offered a substantial discount, but the team was still short. Mutic pushed for launching a crowdfunding campaign. Midway through the conference call, Green’s email pinged. It was a message from ASHA that read, “We need to speak with you as soon as possible.”

With the end of the fiscal year approaching, ASHA had discovered an extra $600,000 that needed to be spent within a week. Just like that, the project was back on.

Almost immediately, the planners hit another snag. The two doctors at INCAN who had helped draft the application had since left the institute and the Washington University team struggled to find anyone at INCAN or the league willing to take over the project.

Frustrated and disbelieving — “Why would anyone turn down a free radiotherapy machine?” Mutic asked. He and Gay flew to Guatemala City to make their case to the league’s board in person. “We were talking and getting nowhere and all of a sudden I realized: They think somebody is getting rich off this,” Gay recalled.

League President Vicky Fuentes de Falla, MD, is a petite, impeccably dressed woman with gracious manners, an abhorrence of corruption and a will of steel. A female doctor in a profession dominated by men, de Falla did not rise to her current position by allowing herself to be snowed. She was adamant that the league would not take part in any kickback schemes.

Gay turned to Mutic and shared his insight. On the whiteboard, Mutic meticulously wrote out all the project’s funding and expenses. There simply wasn’t any money available to be redirected into anyone’s pockets. “Vicky just sat there and looked at the numbers for a while, and then she stood up, smiled, and said, ‘Great, let’s do business,’” Mutic recalled.

Once on board, the league helped fill the remaining gaps, such as funding the remodel of an old cobalt bunker to meet the new machine’s safety and size requirements. Najera filled out the necessary paperwork for permits and licenses from the Guatemalan government. The U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration made an in-kind donation to the project by safely disposing of the cobalt.

After three near-death experiences, the resurrected project lumbered forward.

Opening day

The purchase and delivery of the Halcyon was far from the end of the collaboration. After the machine was installed, two Washington University medical physicists — Bin Cai, PhD, and Eric Laugeman — flew down to INCAN to help with the initial calibration, since they routinely calibrate Washington University’s identical Halcyon system. Najera flew to St. Louis to design treatment protocols in consultation with Mutic and Cai. WhatsApp messages fly cross-continentally whenever problems crop up. Washington University leaders, the league and INCAN are planning more collaborations, such as digitizing the institute’s current paper medical records system.

The morning of the opening ceremony started with a blessing. Gay, Najera, de Falla and a dozen others who had helped bring the machine to INCAN congregated in the newly built bunker. A Catholic priest read a passage about pastoral care of the sick and sprinkled the machine with holy water. The day before, local artist Marie Andrée had finished painting a scene of Lake Atitlán on the wall behind the machine, an iconic image as recognizable to Guatemalans as the Grand Canyon is to Americans.

“My dream is that this hospital should be the best in Central America, for all people, and for free,” de Falla said. “I am proud of the quality of care we have been delivering to all our patients, regardless of ability to pay. With this new machine, we can provide even better care to more people.”

The radiotherapy machine is now working at full capacity, treating 30 patients a day. INCAN’s medical director, Carlos Garcia, MD, keeps a close eye on the machine’s caseload, allocating time to those patients who will benefit the most from the new technology. Yesenia Castellanos has finished her course of therapy and no longer makes the daily trip to INCAN. But every day the machine provides treatment and hope to people very much like her.

Published in the Winter 2020-21 issue