Humans and dogs have lived alongside one another for millennia. Dogs have provided protection and companionship, labor and love. They have worked our farms, hunted our food, guarded our livestock, played with our kids and evolved with us. It’s a unique relationship, unrivaled by any other set of species. And while we may recognize many of the mutually beneficial aspects of this bond, a new paradigm is emerging between man and his best friend: shared medicine.

It’s no secret that animals and people share many of the same diseases. Testing possible treatments for people on animals, especially laboratory mice, is a mainstay of medical research and the origin of most modern therapies.

But physicians are realizing how much stands to be learned by collaborating with veterinarians and designing clinical trials for animals — to treat their naturally occurring diseases — just as we do in people.

The lesson has been embraced by Washington University’s David T. Curiel, MD, PhD, a professor of radiation oncology and of cancer biology. Much of Curiel’s research focuses on the use of engineered viruses to treat disease, especially cancer. He and veterinarians at Auburn University in Alabama are cultivating partnerships they hope will speed the development of cancer therapies for people and their animal companions.

“People love their pets and want to treat them when they get cancer,” Curiel said. “And dogs get cancers that are very similar to human cancers.”

“You don’t put it off…”

It started with a limp. At first, Dawn Oravetz thought her rescue greyhound Gary had simply tripped and bruised his right rear leg. Or, at age 10, perhaps some arthritis was developing in his joints, especially since Gary had spent his early life sprinting around racetracks at 40 miles per hour. Oravetz hoped it was just a bruise, but she had good reason to worry.

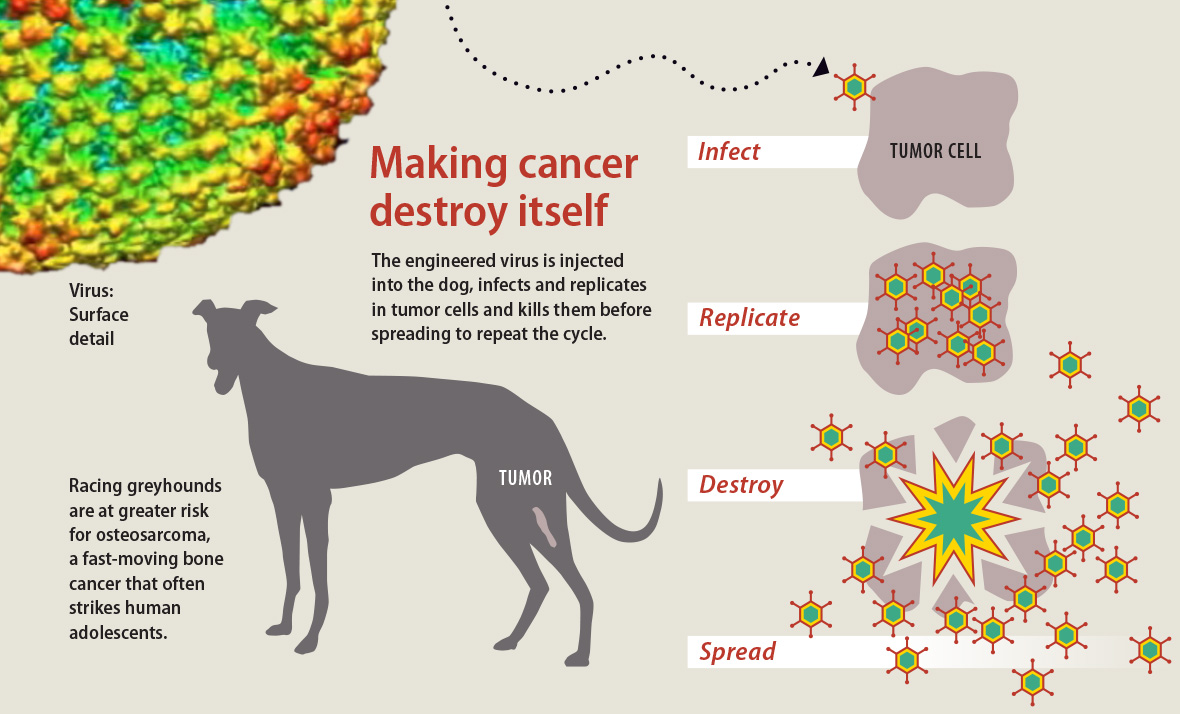

Greyhounds, especially those bred for racing, and other large-breed dogs are at above average risk of developing a type of bone cancer called osteosarcoma. Osteosarcoma is also one of the more common cancers of human adolescence, emerging with teenage growth spurts. In dogs, the tumor tends to be particularly aggressive. Standard treatment is amputation of the affected leg followed by several rounds of chemotherapy. The tumor often spreads to the lungs. Even with aggressive treatment, prognosis is poor. Greyhounds survive an average of only nine months after diagnosis.

Oravetz and her husband, Bill, understood this better than most, already having lost two adopted greyhounds to the disease.

Through contacts in a local greyhound rescue organization, Oravetz learned of a clinical trial at Auburn’s College of Veterinary Medicine, about a four-hour drive from their home in Navarre, Florida.

“We learned from past experience that you don’t put it off,” Dawn Oravetz said. “We found out about Gary’s tumor on a Saturday. And by Thursday, we were at Auburn.”

The director of Auburn’s cancer research initiative, Bruce F. Smith, VMD, PhD, has been collaborating with Curiel for more than 20 years, in an effort to make virus-based cancer treatments a reality for both dogs and people.

A major barrier to research and development of viral cancer treatments is that they cannot be tested in traditional mouse models.

“Human adenoviruses don’t replicate in mice,” Curiel said. “But we thought, what if we take a virus that normally infects dogs and use it to treat dog tumors? Now you have a virus that can replicate in the tumor. The animals have working immune systems and are genetically diverse.

In theory, this fully mimics what we want to do in humans. It’s a more stringent test of the system. And you may end up with a new therapy for dogs in the process.”

Curiel and Smith emphasize that Gary and dogs like him are not experimental animals. As in people, their cancers develop spontaneously, probably due to some interaction between genes and environment. They don’t live in controlled laboratory settings with identical diets. These dogs live at home with their families. And perhaps most importantly for this particular kind of trial, they have intact immune systems, unlike mice so commonly used in cancer research. In short, if a clinical trial of an investigational therapy works in dogs living in the real world, it may be more likely to work in the people who live with them.

As with clinical trials for people, which are voluntary, participation in this trial is at the discretion of the pet owners. Similar to human trials, clinical trials involving animals are overseen and approved by an independent committee that reviews the protocol and decides whether all requirements for ethical disclosure are met.

New collaborators

While the concept of uniting human and veterinary medicine is not new — most recently dubbed the One Health or One Medicine movement — it is beginning to gain new traction in the human medical community. The initiative received a boost in 2012 with the publication of The New York Times bestselling book “Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health.” In it, Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, MD, and co-author Kathryn Bowers argue for increased collaboration between physicians and veterinarians.

Natterson-Horowitz, a cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, noted that veterinarian colleagues at the Los Angeles Zoo often consult human doctors and the medical literature for insights into how best to treat their animal patients. But the reverse — human doctors seeking the collective wisdom of animal doctors and their flagship journals — is a rarity, the authors observed.

In the spirit of shared medicine, Curiel and Smith have developed a trial using a modified version of a common canine virus to treat canine osteosarcoma. Curiel, who also directs Washington University’s Biologic Therapeutics Center, and his team in St. Louis manufacture the viral vectors, freeze them and ship them to Smith.

The therapeutic virus can infect any cell in the body, but it is engineered to replicate in bone tumor cells. Curiel explains bone tumor cells contain a genetic “on” switch required to set the altered virus’s replication machinery into action. Once the virus infects a bone tumor cell, which flips the switch, the virus begins replicating, filling up the cell and causing it to explode.

“We turn the cancer cell into a factory of its own destruction,” Smith said. “Rupturing the cell also sets loose more viruses that are now free to infect other cells.”

Early studies show some promise

To determine if the virus is working as designed, the researchers plan to involve 20 dogs, including Gary, in the current trial. Four dogs participated in a previous, smaller trial to test the safety of the viral treatment, much like human clinical trials start with a phase 1 safety trial. According to Smith, the experience of one dog in particular laid the groundwork for the current trial.

In late 2006, Nancy Hunter noticed the telltale limp in her rescue greyhound, Pretty. After receiving the osteosarcoma diagnosis, Hunter scoured the Internet and found information about the investigational viral treatment available at Auburn. Pretty had the affected leg amputated, received the viral treatment and later underwent chemotherapy.

“She handled the treatment really well,” Hunter said. “After recovering from the surgery, she went back to digging in her sand pile, running around the yard and taking long walks. She got around great on three legs.”

At one year, when Hunter took Pretty for follow-up X-rays, the vets saw two spots on her lungs and suspected the cancer had spread. Upon further analysis, the lesions were determined to be scar tissue. Most significantly, these lesions were possible evidence of an acquired immune response to the tumor.

In addition to rupturing tumor cells with replicating viruses, the treatment may prime the dogs’ immune systems to recognize and attack the virus-infected cells.

“If that is the case, we may be creating an environment that could allow the immune system to start recognizing tumor cells and mount an anti-tumor immune response,” Smith said. “In other words, we’re trying to find out if the dogs become vaccinated against a recurrence of the tumor. That’s the question we want to answer in the current, larger trial.”

Pretty ultimately lived two years and four months after diagnosis, more than twice as long as the average. Smith said there’s no way to know if the experimental treatment was responsible for this. But Pretty’s experience and that of the other three dogs in the first trial allowed them to get funding for the current one.

Very early evidence suggests that a subset of dogs responds well to the treatment. The rest follow the average course. Curiel compares this to human treatments in which only a subset of patients responds well, pointing to the importance of personalized or precision medicine.

A model for human studies

We all want the silver bullet,” Smith said. “But the reality is that cancer is very diverse. This is another reason clinical trials in dogs are excellent models for human studies. All the dogs have different immune systems. They all respond to the world in different ways, just as people do.”

According to Curiel, several other cancers in dogs are excellent mimics of human disease, including melanoma, lymphoma and prostate cancer. Partnering with more veterinarians, including some at the University of Missouri-Columbia, Curiel is working to begin canine trials to test viral therapies in canine melanoma and lymphoma. He is also working with breast cancer researchers to look for ways to improve an investigational vaccine against human breast cancer.

As for the osteosarcoma trial, only time will tell if this treatment strategy shows promise for helping dogs and people alike.

“With osteosarcoma so common in the greyhound community, I think a lot of owners are willing to participate in trials like this,” Oravetz said. “But what really geared me toward wanting to do the study was the idea that what they learn from the greyhounds could potentially help kids with osteosarcoma. If what they learn from Gary could help children with this cancer, I just think that’s an awesome thing.”

Published in the Spring 2015 issue