The seatbelt ripped away Ali Rankey’s abdominal wall in a car accident when she was 20. In the dark months following, Ali endured constant pain, and her prospects for survival were unclear. Professor Emeritus of Surgery Ira J. Kodner, MD, recounts the case to explore life-and-death ethical decision making with enrollees of Mini-Medical School (MMS). The program provides the general public a unique opportunity to hear directly from faculty at Washington University School of Medicine.

As part of Kodner’s presentation, graphic images show sheets of plastic holding Ali’s intestines in place. Attendees wince through the various surgical reconstructions.

But then come the photos of Ali at her college graduation, at her wedding, as the mom of a newborn, and the audience applauds. “Was this a futile case?” Kodner asks.

And then he invites Ali, seated amongst the attendees, to come to the stage. The audience cheers as she makes her way to the microphone. Forty-three surgeries later, Ali now is an elementary school teacher, who says she stresses the importance of a positive attitude to her students.

Turning to Kodner, her voice breaks as she thanks him. Kodner also wells up: “The reason for my living is to keep patients like Ali alive,” he said.

This emotional moment is one of many witnessed by MMS attendees. Now in its 17th year, MMS at Washington University is one of the longest running and most comprehensive in the country.

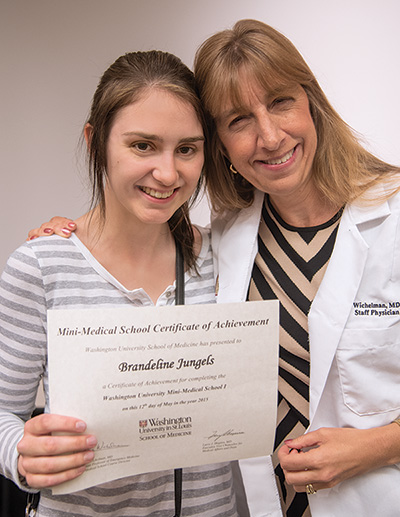

Launched in 1999 by Cynthia Wichelman, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine, the program began with the goal of educating the community on important health-care issues.

As medicine advances at a rapid rate, people are increasingly concerned with maintaining good health and receiving the best possible patient care. Mini-Medical School showcases the Washington University Medical Center, providing the latest information on diseases, wellness, treatments and technological innovation.

“There is a thirst for learning about science and medicine, and curiosity that is difficult to satisfy,” said David B. Clifford, MD, the Melba and Forest Seay Professor of Clinical Pharmacology in Neurology. “However, Cynthia Wichelman is a huge part of the success as she finds talented teachers to share what they know, then recruits and sets up a positive environment for learning. She has done a remarkable job building and maintaining an outstanding program.”

There are no tests and no homework, just eight weeks of easy-to-understand evening lectures from pre-eminent faculty speakers in the Eric P. Newman Education Center and an assortment of hands-on labs and medical center tours. No science background is required. All attendees who complete an eight-week series graduate, earning the honorary title of “mini doc” as “Pomp & Circumstance” serenades.

“I tell people, ‘Just sit back and prepare to be wowed,’” said Florrey Shulman, who has four framed Mini-Medical certificates in her Olivette, Missouri, home.

Conservatively speaking, many of the attendees could be called “super fans.” “Next to having my kids, this is the best thing I’ve ever done,” said Marcie Kalina of St. Louis.

Enrollment is limited to 110 students. Through word-of-mouth recommendations, every rotation sells out and many people are waitlisted. “MMS improves good will by creating a classroom full of ambassadors for the medical center each season and turning them loose on the St. Louis community,” said Bryan Meyers, MD, the Patrick and Joy Williamson Professor of Surgery.

Due to its popularity, the program has expanded to include three different series offered in the spring and fall. The cost is $185 for each.

Quite a few people are repeat customers, cycling through — or even retaking — Mini-Medical I, II and III, as the itinerary shuffles somewhat from year to year. “I found that I learned as much or more the second time around, kind of like re-reading a good book,” said John R. Schott, president of EPIC Systems, an industrial engineering company and fabrication firm.

Mini-Medical students have commuted from as far away as the Missouri Ozarks. One found the information so intriguing she traveled from Chicago to attend 16 sessions, heading back after each on the 4 a.m. train.

The attendees are diverse: stay-at-home moms, CEOs, high school students, retirees, teachers, venture capitalists, artists and police officers, for example. Active and retired physicians also enroll, acknowledging that their expertise is limited to their own specialty.

Simply put, MMS offers experiences that most people aren’t going to find anywhere else. In one session, neurologist Joel S. Perlmutter, MD, using a deep-brain stimulator, makes the manifestations of Parkinson’s disease appear and disappear in a patient as attendees observe.

“The lay public gets a chance to see our doctors ‘up close and personal,’ making our huge medical complex less intimidating,” said Richard Brasington, MD, professor of medicine, adding, “It is the most motivated group of people I have ever taught.”

Afterward, with dessert in hand, students mingle with the speakers and ask questions.

The mini docs, particularly those who complete the entire circuit, may not be ready to practice medicine, but they are well equipped to make better health decisions and converse on a variety of medical topics. Subjects run the gamut — diabetes, cancer, health-care reform, obesity, emergency medicine, depression, heart arrhythmias, minimally invasive surgery, influenza and physical therapy — among many others.

Attendees learn to suture on foam that mimics human skin, tour the Elizabeth H. and James S. McDonnell III Genome Institute, practice the fundamentals of physical exams and handle real anatomy specimens, including brains, hearts and lungs. Highlights are plentiful, but personal stories seem to resonate the most with students, particularly as patients living with diseases such as multiple sclerosis, HIV or cervical cancer share their struggles.

Remarkably, during one such session, John C. Morris, MD, the Harvey A. and Dorismae Hacker Friedman Distinguished Professor of Neurology, invites an Alzheimer’s patient and her spouse to the stage, opening the floor to audience questions that clearly illuminate where the patient’s memories start and stop, and the difference between typical age-related memory loss and Alzheimer’s dementia.

On another evening, Meyers introduces a 56-year-old cystic fibrosis patient named Paul Feld, who tells the story of his double-lung transplant 10 years ago and of his donor, who died at a construction site.

“It was a magical night to see what a wonderful surgical team, a compliant patient and, of course, the gift of life from the donor family, can accomplish,” said attendee Bob Steel, a retired postal worker who has taken I, II and III several times. “Mini Med has given me a brighter, more informed outlook on health care for the future.”

Mini-Med offers “… a great opportunity … to make our work more accessible…”

— Charles F. Zorumski, MD

“When my co-presenter, Paul, talks about the circumstances of his transplant,” Meyers said, “especially about the details of his organ donor, the audience is totally tuned in and with him. It is a compelling part of the story that still grabs me, and I have heard it a dozen times. It is an emotional roller coaster with his discovery of the diagnosis, his decline in capacity, the tragedy of the donor’s situation and the amazing good that has come from the combination of those bad things.”

As Charles F. Zorumski, MD, explains, Mini-Medical School puts a human face on medicine. “This gives us a great opportunity to humanize what we are doing and to make our work more accessible to a bright and interested group of people.”

Zorumski, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of psychiatry, was so struck by the depth of interest from MMS students that he was prompted to co-author the book “Demystifying Psychiatry,” with Eugene Rubin, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, to clarify issues that were raised.

Arnold Bullock, MD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Urology, said MMS has given him a better understanding of how laypeople perceive complex medical problems and, as a result, he has adjusted communication with patients in his daily practice.

Many of the faculty speakers have lectured every year since MMS began. In fact, Ralph G. Dacey Jr., MD, the Henry G. and Edith R. Schwartz Professor and chairman of neurological surgery, gave up World Series tickets to teach at MMS. “It was the Cardinals game that went to midnight, the game one wouldn’t have wanted to miss,” Wichelman said, adding that game updates were announced throughout the evening at MMS.

“I love watching the passion of my speakers,” Wichelman said. “At Mini-Med, the doctors take a break from treating patients for a few hours. Dr. Dacey sometimes comes straight from surgery, dressed in scrubs. The lights come down and he begins speaking and everyone is just riveted, literally taken into another world. Here is Dr. Dacey sharing his tremendous knowledge, years of training and passion. And he is just glowing. Students aren’t the only ones who are transported.”

Clifford agrees. “It gives me a time to reflect and appreciate what I am doing day in and day out. Stopping for a little and trying to explain what this is all about to a non-medical audience also enhances my own appreciation for the privilege I have to be a physician.”

The driving force behind all of this is Wichelman, who logs many hours scouring news sites and medical journals looking for timely topics, querying Washington University medical students about their favorite teachers and sitting in on lectures. “We only put the very best in the MMS lineup,” she said. “This is a real treasure for the community. They learn about medicine in a fun, applicable way, not from the media, but from our experts. We have the best and greatest teachers.”

Wichelman also teaches, sees patients at Student Health Services on Washington University’s Danforth Campus and coordinates the university’s Science On Tap, a non-medical lecture series for the general public at Schlafly Bottleworks in Maplewood, Missouri. She is present at every MMS session, introducing the speakers and shepherding her mini students in a warm, approachable style. “Cynthia is an inspired and enthusiastic advocate for the students in Mini-Medical School, and her exuberance is hard to miss,” Meyers said.

Since 1999, MMS has educated more than 6,000 people. For Wichelman, the payoff has been an engaged public and many forged friendships. She’s now recognized all around St. Louis and often gets stopped in the grocery store or emailed for doctor recommendations.

“One of the joys in my life is getting to know all of the people who take Mini-Med School,” Wichelman said. “These are my kids.”

Some of those kids, like Jason Stephenson, go on to the real thing. Stephenson had graduated from Stanford University and was teaching high school biology when he took Mini-Medical School in 1999.

Inspired by the experience, he applied to Washington University School of Medicine, later becoming class president, and completing a residency at Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. He now is an assistant professor of radiology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Before leaving Washington University, he spoke at Mini-Medical School, of course, to the delight of attendees.

Most MMS graduates — whether licensed to practice medicine or not — say they now are savvier health-care consumers. “As individuals we should take primary ownership of our health and be a resource to family and friends around us in that regard,” said EPIC System’s John Schott. “There are so many things that I have learned in Mini-Med that will undoubtedly allow me to make the best decisions concerning my health over the upcoming years.”

Published in the Autumn 2015 issue