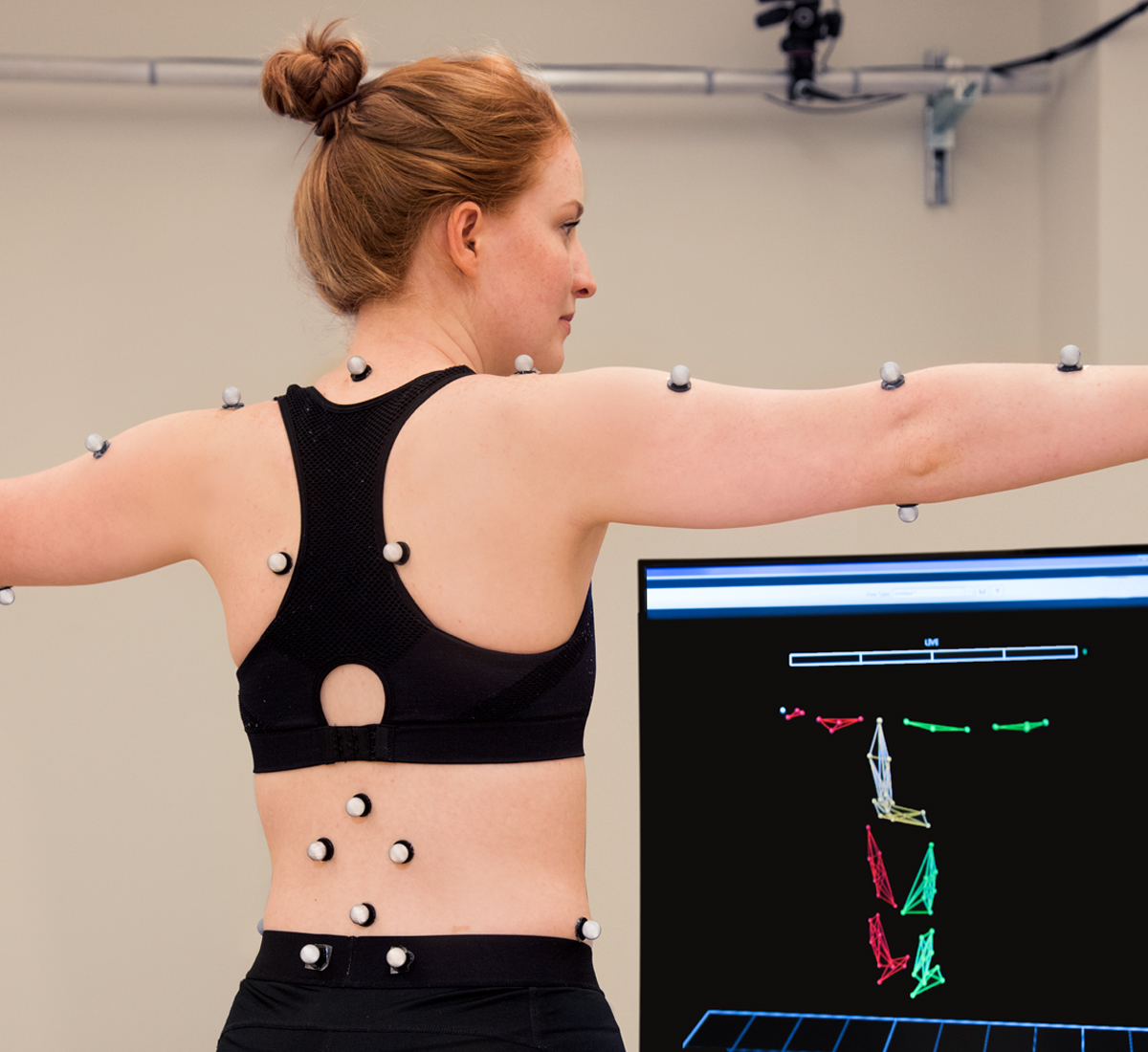

Walking, rising from a chair, reaching for a book — all are simple, everyday movements that many of us take for granted. But for the faculty of Washington University’s Program in Physical Therapy, movement is not something to be taken lightly; it is a central tenet of health.

The physical therapy (PT) program is a national leader in the study of movement and how improper movement leads to injury and impairment. With an emphasis on diagnosing — rather than simply treating patients — the program is changing the way the profession is viewed.

More than three decades ago, faculty members implemented, and have continued to refine, the “movement system” as the basis for the program’s research, educational and patient care initiatives. “At Washington University the movement system really is at the core of all that we do,” said Program Director Gammon Earhart, PT, PhD. “That is unique relative to most other physical therapy programs.

“Our goal is to better understand how the movement system works in health and disease and to understand what we as physical therapists can do to intervene and optimize people’s function through movement,” she added.

In 2013, the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), the leading PT organization, announced it also had adopted the movement system as the foundation for the profession.

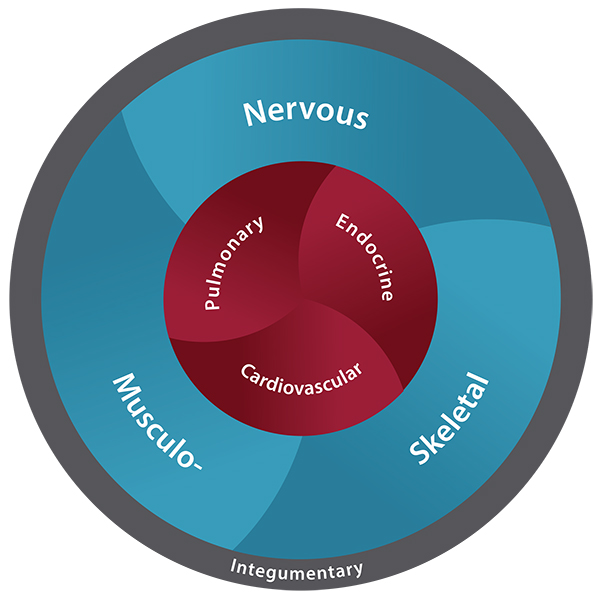

The human movement system

Just as neurologists are defined by their study of the nervous system or cardiologists by their focus on the heart, PT program leaders believe physical therapists should be defined by their study of the movement system. The program defines the human movement system as a collection of body systems (pulmonary, cardiovascular, endocrine, nervous and musculoskeletal) that interact to produce and support movement. Shirley Sahrmann, PT, PhD, FAPTA, professor emerita of physical therapy, has developed and promoted the human movement system both in Washington University’s program and in the profession.

As an active, athletic kid who grew up in the polio era, Sahrmann was deeply affected by stories of people who couldn’t participate in sports or even walk. She has devoted her 50-year career to understanding movement and helping people stay as active as possible throughout their entire lives.

Early on, Sahrmann realized she could reduce pain in patients with musculoskeletal issues by adjusting their movements. “I had to pay a lot more attention to why patients were not moving correctly,” Sahrmann said. This prompted the need for standardized exams and more accurate methods to research and measure movement, which were lacking in the school’s PT program at the time.

So Sahrmann literally wrote the book on the movement system — actually two books, both of which are used in the program’s classes and by health-care professionals worldwide. Sahrmann and others have pushed the field to adopt and associate itself with the movement system.

With the help of her colleagues, she succeeded in getting a definition of the movement system into Steadman’s Medical Dictionary and continued to lobby for its implementation at conferences and in professional circles.

Over the years, the Washington University program has standardized ways to research and diagnose various movement impairment disorders outlined by Sahrmann and others. Sahrmann’s textbooks, considered the gold standard for movement system impairment diagnoses, contain precise diagnostic terminology.

However, some of the more than 200,000 licensed PTs in the U.S. today are working within their own diagnostic frameworks, resulting in confusion. For example, universities that study movement might label their work as “biomechanics” or “pathokinesiology” (the study of abnormal movements), rather than Washington University’s term “movement impairments.” This is one reason why the profession needs a uniform classification system, said APTA President Sharon Dunn, PT, PhD, OCS.

Despite adoption by the APTA in 2013, there are still challenges in getting movement system diagnoses to the patient level and developing a nomenclature that is backed by science. Dunn noted that Washington University’s program is leading the way and improving patient care.

Diagnosis vs. treatment

With most injuries, patients must first see a medical doctor before consulting a physical therapist. The doctor makes a diagnosis such as “low back pain” and refers the patient for therapy services. Traditionally, PTs have used treatments such as massage, heat and exercise to help ease the patient’s pain and restore mobility. In this longstanding scenario, PTs treat, rather than diagnose, their patients.

Faculty members at the School of Medicine are working to change this limited view of PTs as treatment technicians, advocating they instead should be seen as diagnosis-based practitioners with deep expertise in the field of movement science. The movement system provides the framework for PTs to establish themselves as movement impairment diagnosticians.

For example, Sahrmann said, “low back pain” is not a diagnosis; it is a symptom. The underlying cause still must be determined. “You can make people feel better immediately,” Sahrmann said, “but they’re going to come right back because relief doesn’t last unless you really get to the root of the problem.

“Acute pain problems often are just the first warning of a more progressive issue.”

Often the root of musculoskeletal pain stems from repeated incorrect movement in a patient’s everyday activities such as sitting, lifting and walking. Proper diagnosis requires a thorough exam that takes into account a person’s natural way of moving.

Following an exam, a physical therapist might change the “low back pain” diagnosis to “lumbar flexion syndrome,” a condition in which the low back is more flexible than the hips, causing movement imbalances. “So we go through our well established movement diagnostic tests and we show the patient that if you bend in your hips and not in your back, you don’t get symptoms,” Sahrmann said.

Upon understanding the cause of movement impairments, a trained PT can demonstrate the correct way to perform regular activities.

Washington University studies show that patients continue performing these types of everyday life exercises more often than ones that fall outside of normal routines. Patients are more likely to practice the proper way to get up from a chair — something they must do on a regular basis — than perform specific low back stretches requiring them to lie on a mat.

Sahrmann also argues the physician referral requirement needs to change. Many states require physician referral for therapy, though some states, including Arizona, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts and Vermont, have moved toward a self-referral model. Missouri has yet to follow suit.

John Metzler, MD, an associate professor of orthopaedic surgery and of neurology who refers many patients to Washington University for physical therapy, wholeheartedly agrees that PTs are more than technicians. “Most physical therapists have a much broader knowledge of musculoskeletal problems than the average physician because that’s their area of expertise,” he said. “Washington University has excellent therapists who are methodical in how they approach patients. They have a very systematic way of evaluating how patients move, then trying to correct those movements and giving very directed exercises.”

Metzler credits the program’s strong research focus and evidence-based practices.

Moving research forward

Movement science research is a key part of Washington University’s program, which is one of the top-funded in the country. In 2015, the program received more than $3.5 million in research funding, said Michael Mueller, PT, PhD, FAPTA, the program’s director of research. According to the Web of Science, an industry index that compiles publication citation statistics, the program also had more papers cited than any other PT program in the U.S.

“All of our research relates in some way to movement,” said Earhart, who, as president of the APTA section on research, helps translate the program’s research results into practice. Program research ranges from basic studies of how movement occurs on a cellular level all the way to a systems level.

For example, researcher Todd Cade, PT, PhD, is looking at muscle metabolism and function in patients with Barth Syndrome, a genetic disorder that leaves sufferers weak and unable to exercise. Earhart is leading studies that examine the effects of dance and other exercise on improving Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Other trials, such as a study led by Linda Van Dillen, PT, PhD, are exploring the effects of training people with low back pain to modify their movement during daily activities versus having them perform traditional strength and flexibility exercises.

Educational benefits

This research focus is one of the many educational benefits for students, Earhart said. “We are able to attract outstanding students who are drawn to Washington University because of an environment that has a research-intensive focus with faculty who are internationally and nationally recognized for their contributions to the literature and the evidence base for physical therapy,” she added. Currently ranked No. 1 in the country by U.S. News & World Report, the program has been in the top 1 percent for two decades.

Today, all students in the program complete a doctorate in physical therapy (DPT). But this wasn’t always the case. Susan Deusinger, PT, PhD, FAPTA, who retired in 2014 after 26 years as program director, led Washington University’s progression from a baccalaureate-level educational program to a DPT track, which takes about three years and combines clinical, research and classroom learning. More recently, the APTA has mandated that all academic PT programs offer the DPT, a prerequisite to becoming a practicing therapist.

Another major draw for students is the program’s clinical practice, staffed primarily by faculty, said Beth Crowner, PT, DPT, NCS, MPPA, director of clinical practice. “The fact that the people who teach in our clinical courses are still actively engaged in clinical care is a big differentiator for us relative to many PT schools.” Students spend part- or full-time in the clinic with faculty during clinical rotations.

With such strengths in research and the clinic, students come away with a strong foundation in movement system diagnoses. “This program has a rich history of mentoring and developing leaders in the profession,” Dunn said.

The program also shares its research and clinical advances through continuing education initiatives such as an upcoming APTA movement system summit. The summit joins together representatives from U.S. physical therapy programs to think about the movement system and how it can be implemented in curricula, research and practice.

“I think Washington University’s program will continue to be a leader as the movement system becomes more prominent on a national scale,” Earhart said. “And we have a lot of opportunity to help the public better understand who we are and what we contribute.”

VIDEO: The Human Movement System

Published in the Autumn 2016 issue